In the early 1970s, the British intensified their security and military campaigns against the Republican Army in Northern Ireland. Among their tactics were sophisticated deception operations aimed at achieving strategic objectives. The British leadership sought to deepen internal divisions within the organization by undermining trust between the IRA’s seasoned leadership and its younger commanders.

Under the codename “Embezzlement Deception,” a British unit known as the Mobile Reconnaissance Force (MRF) orchestrated an operation that relied heavily on propaganda and disinformation to destabilize the IRA’s internal structure. The “embezzlement hoax” began when British double agent Lewis Hammond approached journalists from the Sunday Times, claiming to be an IRA operative who had infiltrated the MRF on orders from the IRA leadership. Hammond provided detailed information about the MRF’s structure and operations and presented a forged document, purportedly an internal memo from an IRA commander. The document falsely alleged that seven senior IRA leaders had embezzled £150,000 of the organization’s funds.

The leaked document triggered a series of articles in the Sunday Times, fostering suspicion and distrust within the IRA and its wider support network. This disinformation campaign was just the first layer of a broader deception strategy. Additional measures included disseminating misleading information through various channels. For instance, whenever the IRA conducted bank robberies, British officials would deliberately overstate the stolen amount in public announcements. On a more targeted level, double agents fed false intelligence to IRA leaders, further exacerbating internal paranoia.

This example highlights the security dimension and tactical intricacies of deception, which military historian and former U.S. Army psychological warfare officer Barton Whaley defines as “information transmitted through statements or actions to induce a false perception of reality, thereby influencing behavior.”

Whaley’s definition positions deception within the realm of falsification and misinformation. However, a broader perspective—embraced by security experts—suggests that deception is not solely about fabricating falsehoods. Instead, it involves weaving select facts into a larger narrative designed to shape perceptions. According to this view, deception is built upon four key principles: truth, obfuscation, camouflage, and misinformation. The first three rely on presenting real information in ways that prevent an adversary from forming accurate conclusions, while the fourth—misinformation—steers the opponent toward a misleading yet plausible alternative.

For example, by emphasizing and heavily promoting certain facts, other critical information can be obscured, creating a distorted perception of reality. This aligns with the argument of former CIA chief analyst Robert M. Clark, who stated: “All deception operates within the framework of what is true; facts lay the groundwork for perceptions and beliefs, then those facts are used to deceive the adversary.”

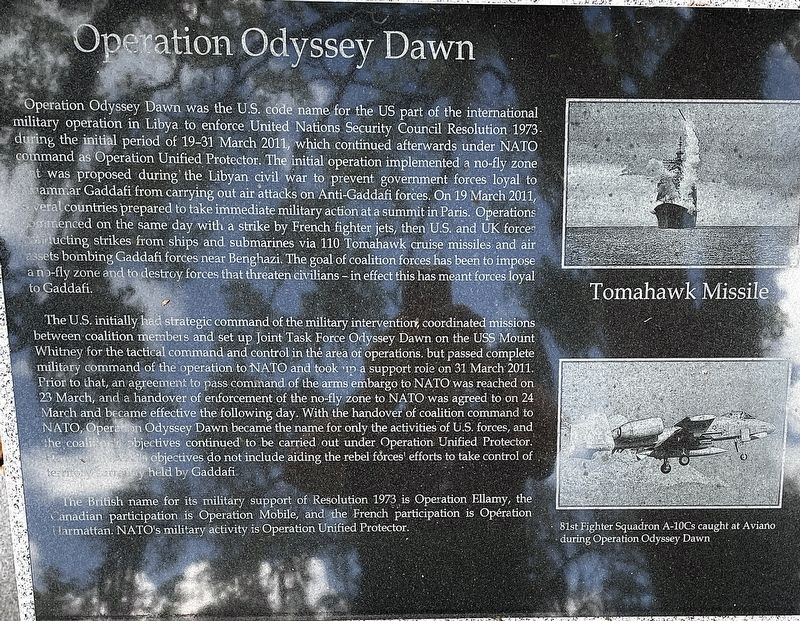

For the purpose of this discussion, we will adopt this broader definition of deception, which encompasses parallel strategies such as psychological operations, obfuscation, and camouflage. These methods extend beyond mere misinformation and aim to manipulate perception and behavior. A striking example of this approach can be seen in a speech delivered by a senior British intelligence analyst to officers and soldiers of the 656th Apache Squadron before NATO’s “Odyssey Dawn” campaign in Libya:

“Your overarching objective in this mission is perceptual influence on the regime. We are not going to win the war with a handful of Apaches, but these aircraft hold significant prestige. You are feared globally, and your periodic appearances in Libya will reinforce that reputation among the target audience in Tripoli. This is where the true impact lies—not in direct combat, but in shaping the regime’s perception. NATO, led by London and Paris, is using the introduction of helicopters to escalate psychological pressure on the regime.”

656th Squadron Commander Will Laidlaw later commented: “The addition of helicopters to the campaign was intended to exert psychological pressure—known militarily as cognitive influence—on the regime’s forces. This was the same reason images of Apaches firing missiles at sea were publicized earlier in the month.”

This example illustrates the comprehensive nature of deception and its wide-ranging applications. While Apache helicopters had minimal operational impact in Libya, their strategic use as psychological tools was emphasized by Commodore John Kingwell, commander of the British Royal Naval Task Force, who confirmed that their primary role was “psychological, not kinetic.” The British naval fleet’s use of high-explosive and precision-guided munitions was similarly aimed at creating a psychological impact rather than achieving direct battlefield effects.

In its broadest sense, deception involves constructing a perceived reality for a targeted individual or group to influence their behavior in a specific manner. This practice spans multiple domains, from military engagements to political and diplomatic maneuvering. Whether in cold wars, open conflicts, intelligence operations, or diplomatic negotiations, deception remains a fundamental and indispensable tool. As the Chinese military strategist Sun Tzu famously stated, “All warfare is based on deception.”

Deception in Diplomacy: While the previous examples focused on military, intelligence, and media channels—areas directly linked to conflict—the strategic application of deception often extends into diplomacy. In this context, deception must be wielded with extreme caution, as diplomatic interactions are traditionally built on credibility and trust. A misstep in diplomatic deception can have far-reaching consequences, not only for relations with the targeted party but also for a nation’s broader international standing.

The English diplomat Henry Wotton once cynically described an ambassador as “an honest man sent abroad to lie for his country,” underscoring deception’s deep roots in international relations. However, while deception is sometimes consciously employed in diplomacy, there are also instances where diplomats themselves become unwitting participants in deception campaigns. In some cases, even the strategic objectives behind their actions remain hidden from them.

Historical examples of diplomatic deception are abundant, particularly during World War II and the Cold War. One of the most notable instances was Japan’s diplomatic engagement with the United States in late 1941. Despite ongoing military preparations for the attack on Pearl Harbor, Japanese diplomats continued negotiations and maintained a façade of cooperation until the very last moment, demonstrating how deception can be a strategic tool in diplomacy as well as in warfare

The pattern of Japanese diplomatic communication suggested that Tokyo had not yet decided to go to war against the United States. This misperception led U.S. political leadership to dismiss intelligence about Japan’s military preparations. Three days before the attack on Pearl Harbor on December 7, 1941, the U.S. president received a warning from naval intelligence indicating that Tokyo’s military and espionage activities were focused on Hawaii.

More recently, negotiations between Hezbollah and the occupying state—mediated by U.S. special envoy Amos Hochstein—offered a unique example of how diplomacy can manage conflict. In this case, Hezbollah’s challenge in maintaining its escalation was not physical but psychological. Its leadership launched an attack on October 8, 2023, with a clear strategic vision and precise calculations. The targeting of Hezbollah Secretary-General Hassan Nasrallah underscored Tel Aviv’s cognitive and strategic advantage.

Strategic Deception in International Relations

As conflict tools and techniques have evolved, the role of deception in international relations has grown in significance. Modern knowledge and technologies enhance the ability to study adversaries, track their movements, and undermine their strategies. This, in turn, necessitates advanced maneuvering and misinformation tactics at the strategic level. At the same time, technological advancements have enabled large-scale deception, making it easier to shape perceptions and control narratives.

The Role of Strategic Deception in Geopolitical Conflicts

The contemporary international landscape—marked by engagement, complexity, and power centralization—has forced various geopolitical actors (states, militias, political groups, and sub-state entities) to develop sophisticated confrontation strategies. Among these, strategic deception plays a crucial role by creating conditions that favor the deceiving party. Unlike short-term misinformation campaigns, strategic deception aims to alter an opponent’s long-term awareness, reducing their ability to interpret events accurately

Deception operations typically serve two primary objectives:

Direct Manipulation – Constructing an alternative “reality” to influence an adversary’s decisions in a way that aligns with broader strategic goals.

Confusion – Disrupting the adversary’s ability to gather reliable intelligence, thereby limiting their capacity for effective action.

The first approach, which involves shaping an opponent’s perceptions, is highly complex, requiring meticulous control over information flow and continuous monitoring of the target’s reactions. The second, a defensive tactic, focuses on obscuring one’s own strategies rather than directing the opponent’s behavior.

The Complexity of Strategic Deception

Most strategic deception efforts aim to construct a distorted perception that leads to long-term confusion. This requires discipline, patience, and persistent efforts to ensure that the adversary remains trapped within a false narrative. The effectiveness of such deception lies in its ability to create a psychological state where even access to accurate information does not immediately correct false impressions. This phenomenon, described as the “Stickiness of Deceit,” can severely impair an opponent’s logic, response capabilities, and policy-making.

A study by the International Psychological Society highlights the difficulty of reversing deeply ingrained misinformation. Human nature tends to defend established beliefs, making it challenging to correct false narratives once they have taken root.

Principles of Strategic Deception

Multi-Level Execution – Deception must operate across political, security, diplomatic, media, and academic domains, requiring strategic cohesion to maintain a consistent narrative.

Continuous Monitoring and Adjustment – Success depends on tracking how perceptions evolve and adapting tactics to ensure the deception remains effective.

Deep Understanding of the Opponent – Effective deception aligns with the adversary’s beliefs, culture, and strategic environment, making the false narrative more convincing.

While deception has operational dimensions, its foundation is cognitive and psychological. It relies on the ability to anticipate and shape an opponent’s perceptions before taking any practical steps.

The Deluge Model: The Art of Storytelling

In 2017, a decade after Hamas took control of Gaza, the movement introduced a document outlining its general principles and policies, presenting itself in a more flexible political tone. This occurred amid significant regional and global shifts, including the resurgence of counter-revolutions, the election of Donald Trump, the reimposition of sanctions on Iran, and the blockade of Qatar. These events created a hostile environment for Hamas, further complicated by the Abraham Accords and the political marginalization of the Palestinian cause.

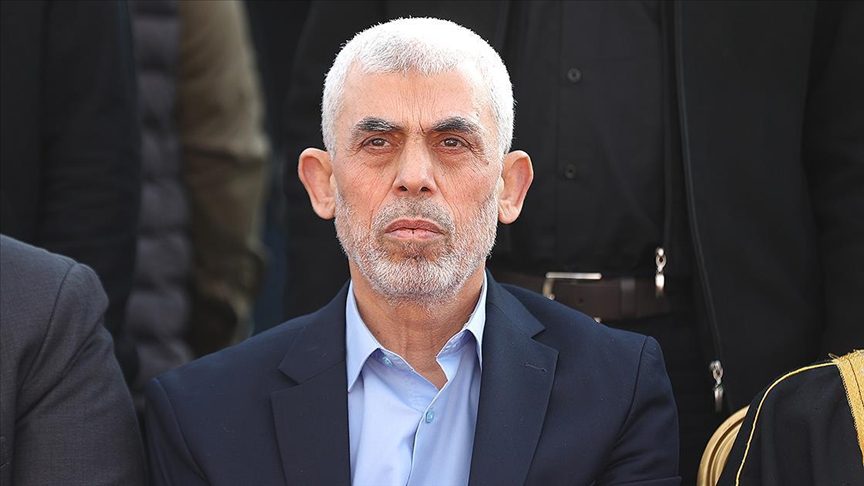

Amid these developments, Yahya Sinwar, a former prisoner and co-founder of the Qassam Brigades, was elected head of Hamas’s political bureau in Gaza. His rise to power was marked by strategic ambiguity, balancing pragmatism with militant rhetoric. Israeli media labeled his ascension as “the victory of the extremists,” with Yediot Aharonot warning that “the safety trigger has been released, and the rifle is ready to fire.”

The Strategy of Deception: Yahya Sinwar’s Approach

Sinwar’s leadership was characterized by an oscillation between conciliation and confrontation. On one hand, he promoted the idea of “peaceful resistance” through return marches, emphasized economic development, and negotiated truces. On the other, he maintained an aggressive stance, ensuring that Hamas’s military buildup continued under the radar.

One of the most striking examples of this strategy occurred during the 2018 truce negotiations. Sinwar personally wrote a letter in Hebrew to then-Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu, urging him to “take a calculated risk.” Meir Ben-Shabbat, Israel’s former National Security Council head, later described this moment as pivotal, as it suggested Hamas’s willingness to de-escalate. Meanwhile, Sinwar was actively strengthening Hamas’s military capabilities.

The Role of Misdirection in Operation Al-Aqsa Flood

Preparing for a large-scale operation in a heavily surveilled and besieged territory like Gaza posed significant challenges. Instead of hiding Hamas’s military preparations outright, Sinwar created a parallel narrative—presenting them as defensive measures rather than preparations for a major offensive. By carefully managing external perceptions, Hamas was able to disguise the true nature of its activities while misleading adversaries into a false sense of stability.

This long-term deception strategy highlights the power of psychological and strategic warfare, demonstrating that in modern conflicts, perception management is as critical as physical military operations.

In the previous narrative, another challenge emerges in the art of deception: how to ensure that the enemy picks up on different signals and swallows the bait (your version of events). Sinwar was determined to address this by creating homogeneity across the various layers of deception. The process involved political discourse, diplomatic communication, security and military measures, propaganda campaigns, modern technology, and other channels, all working together to present a unified message to the enemy. Public policies, internal communications within the movement, and with allies also played key roles in reinforcing the central message of “peace and weathering the storm.” It was a complex process that required careful practice.

Additionally, the military strategy played a pivotal role, particularly the decision to refrain from participating in several rounds of confrontation with the occupying forces. This became a defining feature, shaping the enemy’s perception of the movement’s “new” direction. Hamas’s refusal to engage in confrontations led by the Islamic Jihad movement and the Jerusalem Brigades, including the May 2023 escalation, marked a turning point in how the enemy understood the movement’s true intentions. This pattern suggested a shift away from a strategic concept that Hamas had once embraced as a defensive measure against efforts to isolate the resistance and the Palestinian cause.

The impression created was that Sinwar’s rhetoric of confrontation and limited engagements were tactical, part of a broader “review” of the movement’s strategic position. Any escalation, whether rhetorical or kinetic, seemed aimed at improving negotiation options and preserving internal cohesion and reputation—far from signaling preparations for major confrontation. The general impression was that Sinwar “did not mean what he said.” This perception framed how the occupation leadership interpreted all movements and preparations, leading them to ignore critical intelligence about the preparations for the Al-Aqsa Deluge operation. Despite multiple warnings from military intelligence (“Aman”) and internal intelligence (“Shabak”) between March and July 2023, as well as Egyptian intelligence alerts just days before the attack, Israeli leadership dismissed these warnings. A statement from the Israeli Prime Minister’s Office downplayed these allegations, claiming they had shared the information with security agencies but dismissed the concerns about Hamas’s plans.

Sinwar successfully conveyed this narrative, countering regional and international opposition, and shielding the military infrastructure of the resistance. His ability to pass this deception relied on his deep understanding of the enemy’s culture, mindset, and evaluation methods. His experience, forged over 23 years in Israeli prisons, and his leadership roles within the movement—both politically and militarily—played a crucial part in his success. Sinwar, who founded the anti-agent apparatus “Majd” in the 1980s, built a reputation of respect among security and military leaders. He also linked the political and military wings of the movement and held a wealth of experience in negotiating and understanding the occupation. These qualities allowed him to contribute to the movement’s strategic planning and bolster its core values, external relations with allies, and internal belief in his leadership.

It’s no exaggeration to say that the Al-Aqsa Deluge operation will be remembered as one of the most successful examples of strategic deception. This is not just because the operation’s leadership adhered to the principles of deception, but because of the challenging circumstances under which it was carried out. The operation took place amidst a harsh siege—geographically, security-wise, politically, and ideologically—with a massive imbalance of power and resources. Despite the forces of normalization and counter-revolution and the diminishing influence of revolutionary and Islamic states, Sinwar’s leadership allowed the movement to adapt without sacrificing its core values and strategic goals.

Conclusion

From the British experience with the Irish Republican Army, to Japan’s diplomatic disinformation before Pearl Harbor, to the Lebanese-Israeli negotiations that led to dropping “red lines,” to the Al-Aqsa Deluge model, all these examples highlight how strategic deception can overcome power disparities and create major shifts in the surrounding environment.

The Al-Aqsa Deluge model illustrates three key conclusions:

The critical role of strategic deception, especially in situations of vulnerability—whether geographical, security-related, or in a hostile political environment.

The movement’s leadership effectively utilized all available tools, from statements and political speeches to diplomatic communications and negotiation strategies, to shape perceptions that enabled the execution of a complex operation under a cover of misleading narratives.

A single successful operation can turn the tide, overturning long-held strategic assumptions and dropping red lines previously thought to be invulnerable.

Ultimately, strategic deception proves that conflict is not solely about material power, but also a battle of wills and minds. When the deceptive side succeeds in misleading its opponent and shaping false perceptions of reality, it can achieve a decisive strategic advantage in the conflict and its outcomes.