In the smoke-filled aftermath of Sambhal, where the echoes of police gunfire still haunt its streets, the complicity of India’s judiciary in enabling a divisive political agenda must be laid bare. Five lives—five young Muslim men—were taken under the pretense of maintaining “law and order.” This massacre is no isolated incident. It is the grim result of a calculated erosion of constitutional protections, spearheaded by political opportunism and judicial timidity, if not outright collusion.

At the center of this tragedy stands a figure who once bore the weighty mantle of Chief Justice of India: D.Y. Chandrachud. His tenure, particularly marked by his judgments and remarks concerning the Places of Worship Act of 1991, has emboldened those who seek to rewrite India’s history and unravel its secular fabric.

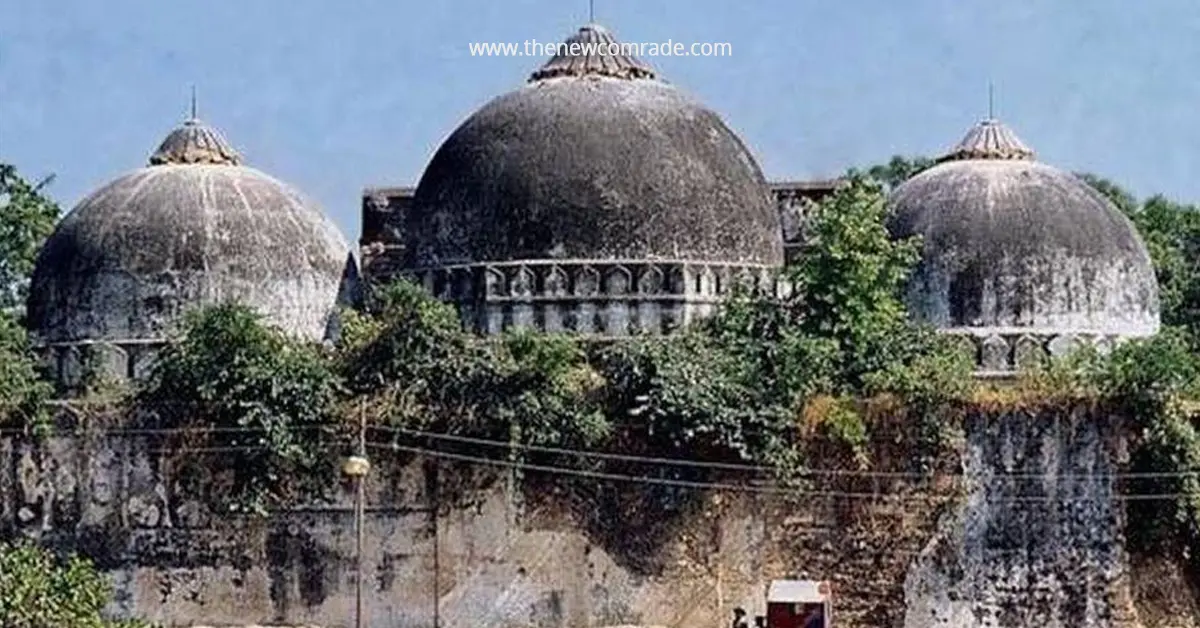

To comprehend the gravity of Chandrachud’s actions, one must revisit his controversial decisions, starting with the Gyanvapi mosque case. The 1991 Places of Worship Act was envisioned as a bulwark against the endless cycle of religious vendettas, ensuring that the status quo of all places of worship as of August 15, 1947, remained intact. Its passage was an attempt to prevent another Babri-like catastrophe, where the demolition of the Babri Masjid in 1992 catalysed riots, bloodshed, and deepened societal fissures.

Yet, Chandrachud’s Gyanvapi ruling in 2023 cracked this shield. His court greenlit the Archaeological Survey of India’s investigation into the mosque, under the pretext of ascertaining its historical character. Critics immediately pointed out that this was not a simple archaeological exercise but a blatant political maneuver disguised as legal procedure, meant to lend legitimacy to Hindutva claims of historical grievance.

In a statement, Chandrachud remarked, “The Act says you can’t alter or convert the nature of the place. They’re not seeking conversion of the place. The question is what is the status of the place as of August 15, 1947.” With this seemingly innocuous observation, Chandrachud opened Pandora’s box. His interpretation effectively gave Hindutva forces a legal framework to question the integrity of Muslim places of worship across the country.

The immediate fallout of Chandrachud’s judgments has been catastrophic. In Sambhal, a court-ordered survey of the 16th-century Shahi Jama Masjid, instigated by Hindutva groups, became a flashpoint for deadly violence. The survey was based on the unsubstantiated and inflammatory claim that a temple once stood at the site, a claim weaponized to inflame communal passions.

This judicial endorsement has not only validated these fringe narratives but has also militarized them. When a Hindutva mob accompanies a court-sanctioned survey team, chanting provocative slogans like “Jai Shri Ram”(Hail to Ram), it is clear that these are not mere legal formalities. They are provocations, intended to incite fear, resistance, and ultimately violence. Sambhal is but the latest victim of this toxic nexus between judiciary-sanctioned revisionism and Hindutva aggression.

The deaths in Sambhal were not random; they were deliberate. Naeem, Mohd Bilal Ansari, Noman, Ayaan, and Mohd Kaif were executed by a state apparatus emboldened by a judiciary that has abdicated its responsibility to uphold constitutional values. These young men are martyrs in a war against India’s pluralistic soul.

What is most damning is the judiciary’s active role in legitimizing these attacks under the guise of constitutional propriety. The Gyanvapi case is not an anomaly; it is a continuation of Chandrachud’s troubling judicial legacy. Under his stewardship, the Supreme Court also refused to stay the Allahabad High Court’s orders for surveys of the Shahi Idgah mosque in Mathura.

This willingness to entertain claims from Hindutva petitioners, while dismissing the concerns of Muslim litigants, reflects a deeply skewed sense of justice. Legal scholar Dushyant Dave minced no words in a recent interview, accusing Chandrachud of doing a “great disservice to the Constitution.” Dave’s tears are a reflection of the deep betrayal felt by many who had once hoped the judiciary would act as a counterweight to the state’s oppressive tendencies.

The judiciary’s recent trajectory raises uncomfortable questions. Is it merely inept in dealing with politically sensitive cases, or has it become an active collaborator in the Hindutva project? By allowing these surveys and investigations, the courts are providing a veneer of legal legitimacy to what is essentially a campaign of religious persecution.

The consequences of these judicial missteps are far-reaching. Every new petition questioning the legitimacy of a mosque emboldens Hindutva activists to push further, to demand more. What stops the judiciary from seeing that these claims are not about history or archaeology but about power? They are attempts to displace Muslims, both symbolically and physically, from the Indian public sphere.

Sambhal is already witnessing the consequences. Internet shutdowns, prohibitory orders, and the silencing of dissent are now the government’s default response to unrest. But these measures only serve to deepen the divide, fostering a sense of alienation and victimhood among the country’s Muslim population.

Former CJI Chandrachud’s defenders may argue that he merely followed the letter of the law, that he was duty-bound to entertain petitions and adjudicate them. But this defense rings hollow. Chandrachud’s decisions reveal a pattern of interpretation that consistently undermines the constitutional principle of secularism. His rulings on the Places of Worship Act have weakened its protective framework, allowing Hindutva forces to exploit legal loopholes to further their agenda.

This is not the impartial justice the Constitution demands. It is a selective application of the law, one that disproportionately harms minorities while empowering their oppressors. The judiciary, under Chandrachud, has failed in its duty to act as a guardian of constitutional morality. Instead, it has become a willing participant in a project of majoritarian consolidation.

The role of the Uttar Pradesh government in this crisis cannot be overstated. Under the leadership of Chief Minister Yogi Adityanath, the state has transformed into a laboratory for Hindutva policies. The police firing in Sambhal is not an aberration but a feature of this governance model, which uses state violence to suppress dissent and enforce communal hierarchies.

Statements from political leaders like Samajwadi Party chief Akhilesh Yadav and Congress leader Rahul Gandhi have rightly condemned the BJP for orchestrating this violence. Gandhi’s assertion that the BJP is “directly responsible” for the killings in Sambhal underscores the party’s role in engineering communal strife to divert attention from its policy failures and consolidate its voter base.

Perhaps the most poignant indictment of India’s judiciary came not from a courtroom but from the tearful eyes of senior advocate Dushyant Dave. His anguish was palpable as he accused former CJI D.Y. Chandrachud delivered rulings that have eroded India’s secular foundation. Dave’s tears were not just for the victims of Sambhal or the desecrated sanctity of Gyanvapi but for the millions of Indians who still believe in the judiciary as the last bastion of justice.

Dave’s emotional plea is a clarion call for introspection within the judiciary. His tears, a rare public display of grief and rage, highlight the profound sense of betrayal felt by legal professionals and ordinary citizens alike. They serve as a stark reminder that when those entrusted with safeguarding justice falter, the repercussions are felt not just in the courtroom but in the streets, the homes, and the hearts of the people. If the judiciary continues down this perilous path, Dave’s tears may well become the requiem for India’s constitutional democracy.