Every January 2 is an occasion to relive the memories of Andalusian catastrophe, which keeps overshadowing us. Here, we aim to present a “historical picture” that helps facilitate and simplify history of Andalus, by reviewing maps of the stages of its rise and fall.

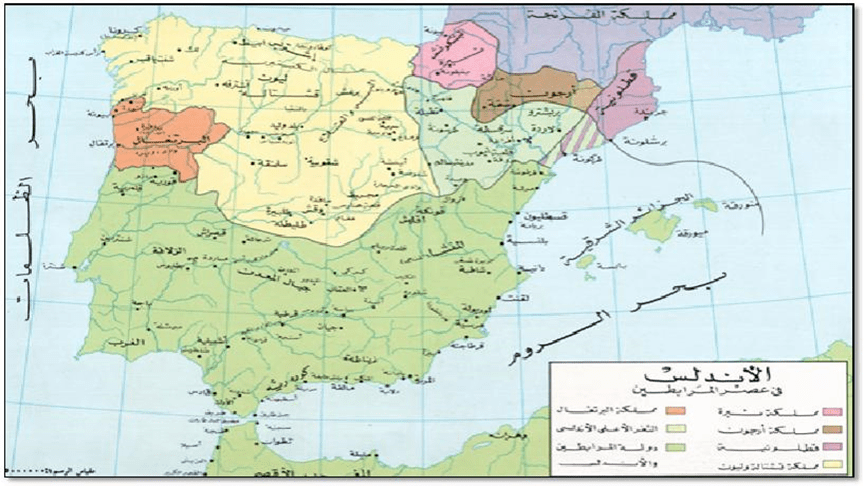

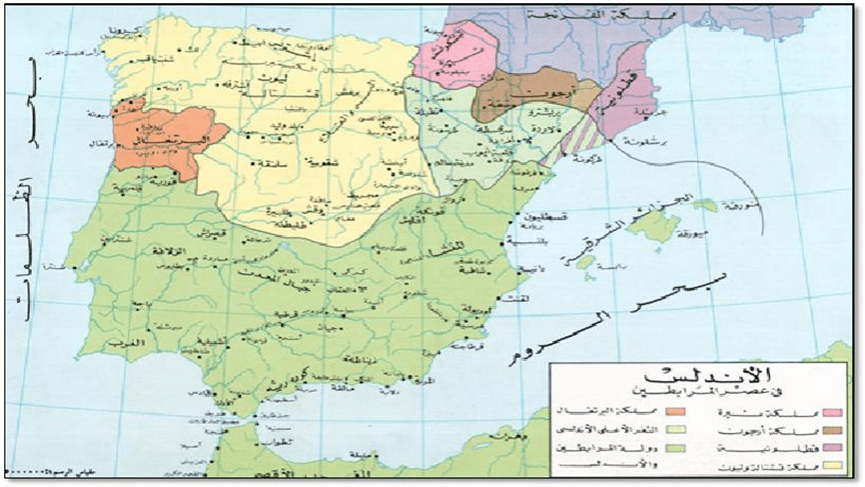

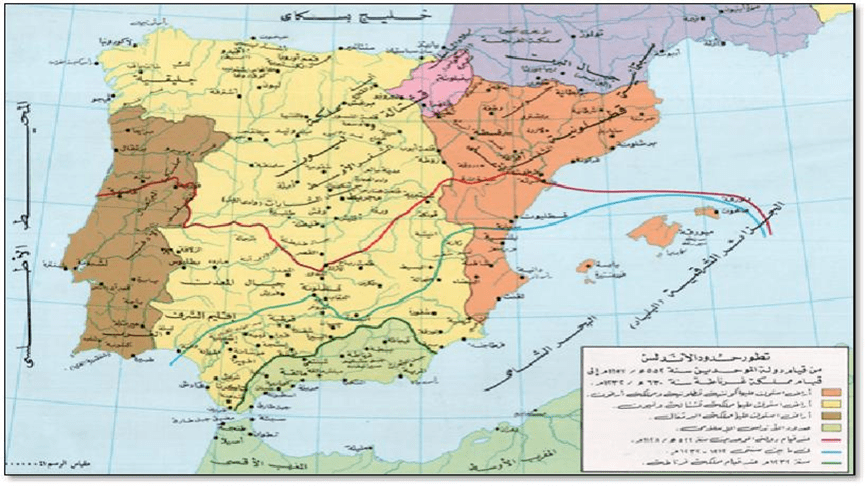

We could divide Andalusian history to eight stages: Muslim conquest, era of governors, Umayyad period, Aameri state, era of “taifah” states, Almoravid (Morabet) state, Almohad (Mowahed) state, Ahmari state of Granada and final fall on January 2, 1492 CE.

Muslim Conquest

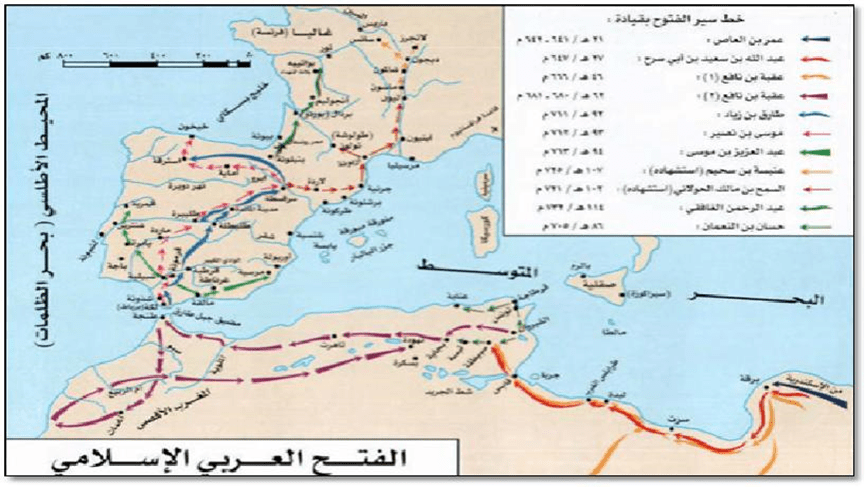

In 92 AH, an army led by Tariq b. Ziyad – a Berber of a lineage that embraced Islam during the conquests of Maghreb – was dispatched by Abd el-Aziz b. Musa, the Umayyad governor of North Africa, to begin the conquest of Andalus. This came after the children of its Vandal ruler appealed for help in face of a military coup led by Roderic (or Lodrig), resulting in the Muslims’ first entry into Andalus. They achieved a decisive victory in the battle against Roderic’s forces, and the cities surrendered without much resistance. The conquests continued through Umayyad governors like Samh b. Malik, Anbasa b. Suhaym, and Abdur Rahman al-Ghafiqi, extending to the south and central France (“Gaul”), halting just kilometres from Paris after the Muslims’ unexpected defeat at the Battle of Poitiers (“Balat ash-Shuhada”; 114 AH / 732 CE) by Charles Martel – which is considered the beginning of “crusades”.

Below map depicts these stages of conquest.

Source: Dr. Shawqi Abu Khalil: Atlas of Arab-Islamic History

Era of Governors (Wali)

In this period, Andalus used to be governed by governors appointed by the Umayyad caliph at Damascus. Some of the most prominent governors were Samh b. Malik, Anbasa b. Suhaym, and Abdurrahman al-Ghafiqi. They were succeeded by weak and incapable governors, implanting in them tribal conflicts, injustices towards public and rebellions and revolts by Kharijites and others. Despite efforts from Umayyad centre at Damascus, especially coming at time of their own weakness, they could not resolve these issues. As a result, Muslims were punished by Allah by loss of all territories they had conquered in France. Rather, remnants of the past order held up in the northwest mountains took advantage of the situation and expanded to sow seeds of what would later become hostile dominions within the Andalus peninsula, as represented in the below map.

Map source: Dr. Husein Moanes: Atlas of Islamic History

Umayyad Era

When the Abbasid revolution succeeded in overthrowing Umayyad dynasty in the Eastern Muslim lands, a young Umayyad – viz. Abdurrahman b. Mu’awiyah (also called “Abdurrahman I”, “Dakhel”) – no more than twenty-one years of age, managed to escape. He possessed talents, resilience, and perseverance that enabled him to flee, from the Abbasids’ relentless pursuit, all the way to the farthest parts of Western Muslim lands. From there, he established contact with the Umayyad supporters in Andalus, and through a combination of strength, politics, and determination, he was able to establish a state on his own in Andalus – thus reviving Umayyad era in the West after its demise in the East. In doing so, he saved Andalus from an imminent fall it was heading to, due to the weakness and tribal fragmentation there. He founded a strong, awed, and stable state. However, he was unable to reclaim territories lost in northern Andalus and south and central France. However, this moment marked a new birth for Andalus, as a shining civilisation.

Umayyad period in Andalus lasted for about two and a half centuries (137–422 AH). The first century of this period was marked by strength, lasting until the end of reign of Abdurrahman b. Hakam (also called “Abdurrahman II”, “Awsat”; 238 AH). Thereafter, weakness began to creep in, with revolts, uprisings, and fragmentation of power for nearly two-thirds of a century. It was reversed only when Abdurrahman b. Mohammed (also called “Abdurrahman III”, “Nasir li deenillah”), a young man in his twenties, took power. He restored the strength of his forefather, Abdurrahman b. Mu’awiyah, and drew Andalus to the peak of its power, surpassing its past levels of wealth and civilisation. He ruled for half a century (300–350 AH). His son, Hakam b. Abdurrahman, (also called “Hakam II”, “Abul ʿAaṣ”, “Mustanṣir billāh”) —was more knowledgeable than his father, passionate about knowledge, books, and various sciences and continued the strength of the Umayyad state for sixteen years. With his demise, his son still young, Andalus entered the phase of “Aameri state”.

Both ‘Nasir’ and ‘Mustansir’ were able to restore the domains of Andalus as established by their founding father, with the complete political submission of the northern Christian dominions. Therefore, we do not see much change compared to the previous map.

Aameri State

Aameri state is considered part of the Umayyad period because of the nominal and official sovereignty being in the name of the Umayyad caliph, while actual power existed with Muhammad b. Abdullah (variably called “ibn Abu Aamer” “Hajeb” “Almanzor”, “Mansur”). This man was an extraordinary and remarkable figure, multi-talented, highly ambitious, sharp-witted, and determined. He excelled in every task he undertook, surpassing experienced hands. He succeeded in managing everything: documentation, judiciary, overseeing caliph’s private estates, state finances, police, administration of the city of Córdoba, diplomacy, ministry, chamberlain (which gave him his title “Hajeb”), leadership of armies. I know of no comparable figure in whole Muslim history. Mansur managed to earn initial patronage of the minor ruler’s regent mother – Sabihah / Sub’h, and thereafter seized power and brought Andalus to the zenith of its strength. In his twenty-seven-year reign, he led fifty-six military expeditions with no defeats. He expanded Andalus’ influence further into northwest Africa. He later entrusted the position of chamberlain to his son, Abdulmalik (“Mudhaffar billah”, “sayf ad-dawlah”) whose reign maintained the same power as father. However, he died just six years into his reign, still a young man, and his brother, Abdurrahman, took over the chamberlain position. Abdurrahman was rash and short-sighted, leading to the collapse of Aameri state, and Andalus entered an era of turmoil.

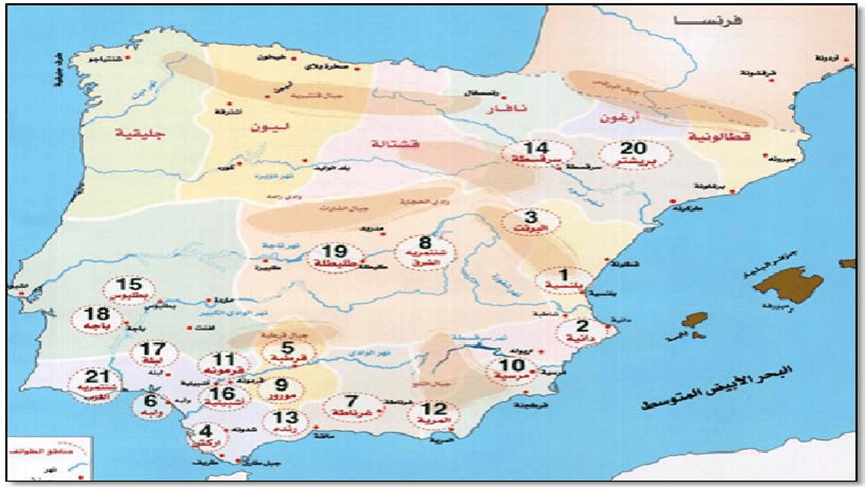

Era of “Taifah” states

None of the subsequent Umayyad caliphs were able to reunite Andalus, marking the dusk of Umayyad legacy, which formally ended in 422 AH. In this stage, Andalus entered the era of “Taifah” states.

During this period, Andalus was divided into more than 20 provinces, each ruled by the most powerful faction in it. Stronger of these were: Seville, ruled by Banu Abbad; Córdoba, ruled by Banu Jawhar; Badajoz, ruled by Banu Aftas; Zaragoza, ruled by Banu Hud; and Toledo, ruled by the Banu Dhun-nun. These factions fought amongst themselves. Correspondingly, Christian states of the northwest were building their strength and starting their long crusade “Reconquista” project.

Although Christian states fell into discord again after the death of Ferdinand, taifah states did nothing to regain the lost territories. Toledo even welcomed Alfonso VI, the son of Ferdinand, who had fled from his rival brother. He was able to reach out to his supporters and return as king, resuming his father’s “Reconquista” project. His first major move was the capture of Toledo itself, the most significant blow to Muslim presence since the conquest of Andalus!

Fall of Toledo was a devastating shock to the Muslims, and taifah states were being sacked by Alfonso one after the other. Seville ruler had no choice but to seek help from the Almoravid state of northwest Africa to aid them in repelling Alfonso – who had reached to his borders.

Map source: Dr. Tareq Suwaidan: Andalus… Illustrated History

Almoravid era

Yusuf b. Tashfin responded to the call for help from the remaining taifah chiefs and crossed the Gibraltar strait with his army to Andalus. He fought one of the most brilliant battles in Islamic history, viz. Battle of Zallaqah (“Zalaca” / “Sagrajas” ; 479 AH), which enabled him to save Andalus for at least a century. In this battle, Alfonso VI’s forces were crushed. Yusuf b. Tashfin crossed into Andalus multiple times to heed calls for help, engaging in other lesser critical battles. These were not enough to deter taifah chiefs from their vices. They continued their misdeeds, even submitting themselves as tributaries to Alfonso, and imposing heavy taxes on their own subjects. As a result, religious scholars from Andalus, northwest Africa, and the broader Muslim world issued a religious rulings urging Yusuf b. Tashfin to enter Andalus and remove taifah chiefs – which he did. Almoravids brought about unification of Andalus and northwest Africa, after they had previously united the fragmented regions of northwest Africa to one strong state.

However, Almoravid rule in Andalus did not last long – waning after about forty years. Then, a new movement emerged in Morocco, which turned into a state that was able to overthrow the Almoravid rule, first in Morocco and then in Andalus viz. Almohads.

Almohad Era

Almohad movement began in Morocco under the leadership of “Muhammad b. Tumart,” and it quickly attracted the support of the Masmuda tribes, which became the driving force behind this movement. They began overthrowing Almoravids gradually. Almohads inherited Andalus, along with the other territories of Almoravid state, but the period of warfare between Almoravids and Almohads had serious repercussions in Andalus, with some Andalusian cities falling into the hands of the Crusaders.

Under Yaqub al-Mansur, Almohads fought a memorable battle similar to Zallaqah, called Battle of Arak (Alarcos ; 591 AH), in which Alfonso VIII’s forces were crushed. However, just three years later, Yaqub al-Mansur passed away, and his state went into decline. Only eighteen years after the great victory at Arak, Almohads suffered a crushing defeat at the Battle of Uqab (609 AH), which led to devastating consequences. It was said that no youth in Andalus was left capable of fighting after this battle.

While the fall of Almoravids was followed by the rise of Almohads, the fall of Almohads was not followed by the emergence of a strong state in northwest Africa. The subsequent rulers had become symbols of excessive devotion to power, neglect of their territories, and reliance on the Crusaders under any terms. As a result, Andalusian cities fell in a painful, dramatic, and successive manner without receiving any help. In 623 AH, Baeza fell, followed by the island of Mallorca and Badajoz (627 AH), Mértola (628 AH), Algeciras (630 AH), Estepa and Medina- Sidonia (633 AH). In the same year, Córdoba, the magnificent capital of Islam and the jewel of medieval Europe, fell, followed by Valencia (636 AH), Murcia and Algeciras (640 AH), Dénia and Alicante (641 AH), Orihuela, Cartagena, and Jaén (643 AH), Chitiva (644 AH), Seville (646 AH), and the western Taifah of Santarém (647 AH), among other middle and small cities. The only remaining Muslim state in Andalus was Granada.

Ahmari state of Granada

Unexpectedly, the small state of Granada managed to survive for about two and a half centuries before the final fall. Muhammad b. Ahmar was able to establish a state in Granada under difficult circumstances and humiliating terms with the Crusaders. At the same time, he received a third wave of assistance from northwest Africa, namely from Marinid dynasty, which repeated Morocco’s earlier role in saving Andalus. While the Marinid state was not as powerful as Almoravids or Almohads, it did carry out a battle similar to Zallaqah and Arak, which helped preserve Andalus presence for a long period. This battle was the Battle of Dununiyah (Ecija ; 674 AH) led by Yaqub al-Mansur, a Marinid ruler. Moreover, the Marinids established a permanent presence in Andalus to support Granada.

Additionally, internal conflict among the Christian warlords helped Granada survive for a longer time. Had this conflict occurred during the period of Almoravid or Almohad states, it is more likely that they would have regained lost territories.

However, with the general weakening of both Granada and northwest Africa, Castile managed to seize the Gibraltar strait, cutting off any formidable support for Granada. Gradually, Castile began tightening its grip on Granada. When the Kingdoms of León and Castile were united through the marriage of Ferdinand and Isabella, the creation of Granada was setting. Granada collapsed after a year and a half of intense siege, marking the end of the only period in Spain’s history when it had a flourishing civilisation on the world stage. Muslims lost Andalus, and the world lost a brilliant civilisation that served as a contrast to European “dark medieval” ages.

Translated by Reem Al Haddad (Gaza)

Originally published in author’s blog

Disclaimer: The opinions expressed in this article are solely the author’s and do not neccessarily reflect the opinions or beliefs of the website and its affiliates.