The Ali Brothers, Dr. Kitchlew (Punjab), Shri Shankeracharya of Sharda Mutt, Maulana Hussain Ahmed of Deoband, Pir Ghulam Mujaddid, and Maulana Nisar Ahmed were indicted for criminal conspiracy, promoting enmity to Government, and attempting to seduce the troops from their allegiance.

The indictment was based on the following resolution passed by the Khilafat Committee on 9th July 1921:

“This meeting clearly proclaims that it is in every way religiously unlawful for a Mussalman at the present moment to continue in the British Army, or to enter the Army, or to induce others to join the Army. And it is the duty of all Mussalmans in general and of the ‘Ulema in particular to see that these religious commandments are brought home to every Mussalman in the Army.”

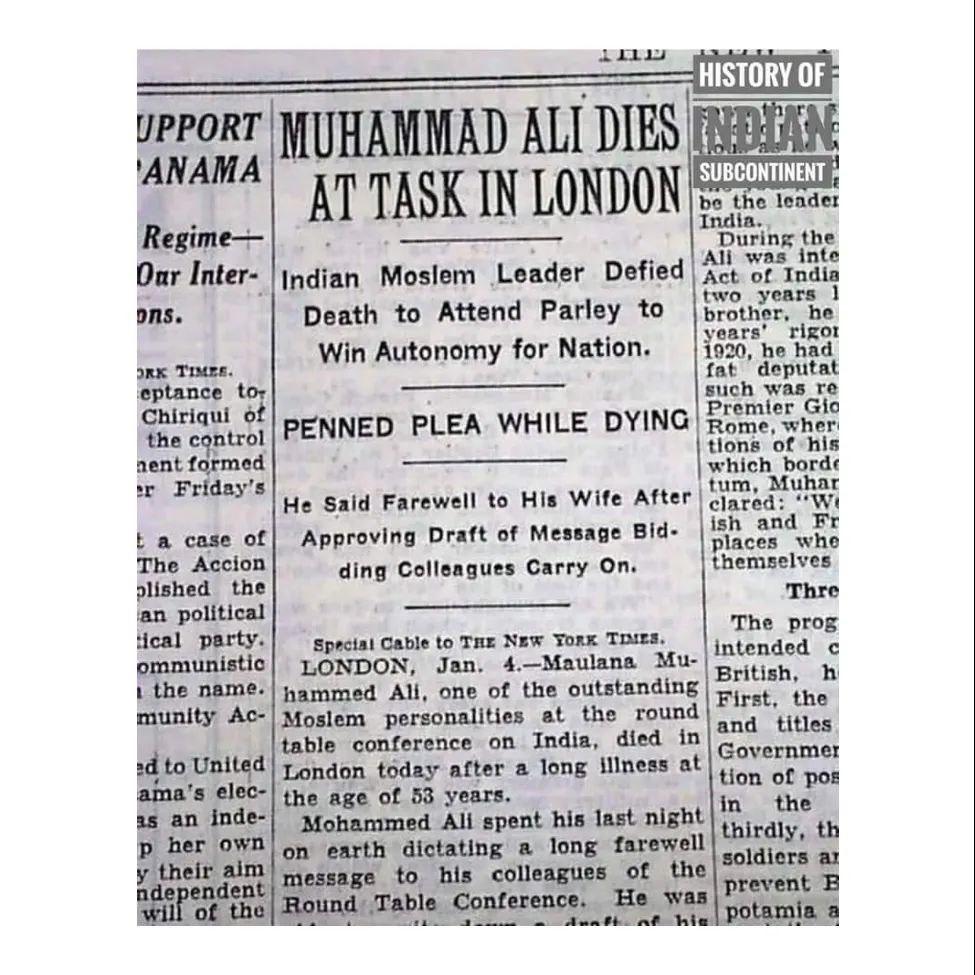

The Sessions trial opened at Karachi on October 26, 1921. It created the most widespread interest in the country within living memory. The Indian press assigned precedence to the event over every other item of news.

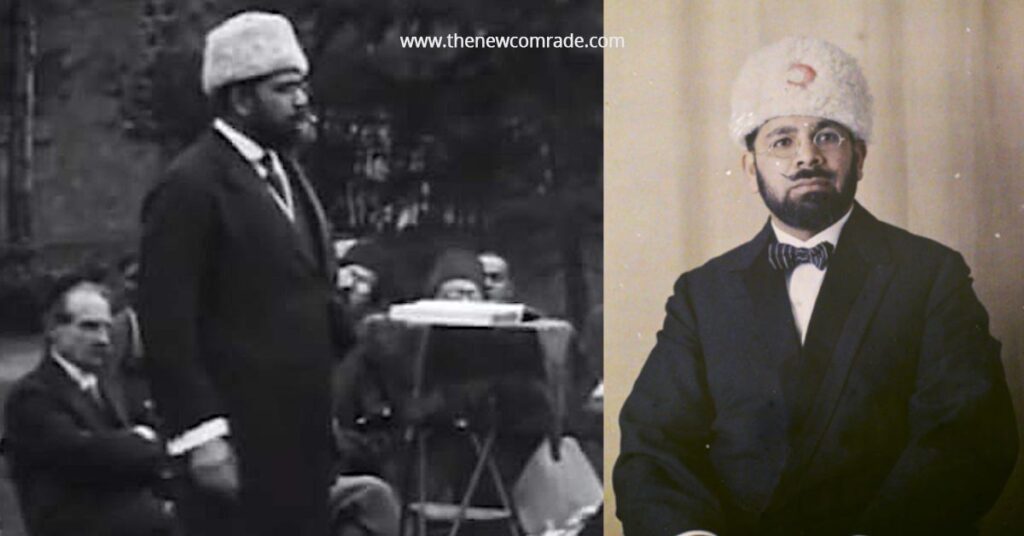

Mohammed Ali addressed the jury to answer the accusations against him and his co-accused. This address is widely acknowledged as a masterpiece in advocacy.

The jury, after anxious deliberation, returned a verdict of “not guilty” under the principal charges of conspiracy and seduction of soldiers but pronounced “guilty” under the minor charges of causing mischief, etc., significantly adding at the same time that they did not take into account the deep-rooted Muslim sentiments in the matter.

On November 1, the judge pronounced his judgment. He agreed with the jury’s verdict, acquitted the accused under the serious charges, but convicted them for the minor offences of causing mischief, abetting offence, etc. He sentenced Mr. Muhammad Ali to two years’ rigorous imprisonment.

The following is the first part of the lengthy address. Other parts will be shared in subsequent posts. We need to learn from our predecessors.

ADDRESS TO THE JURY – Part 1

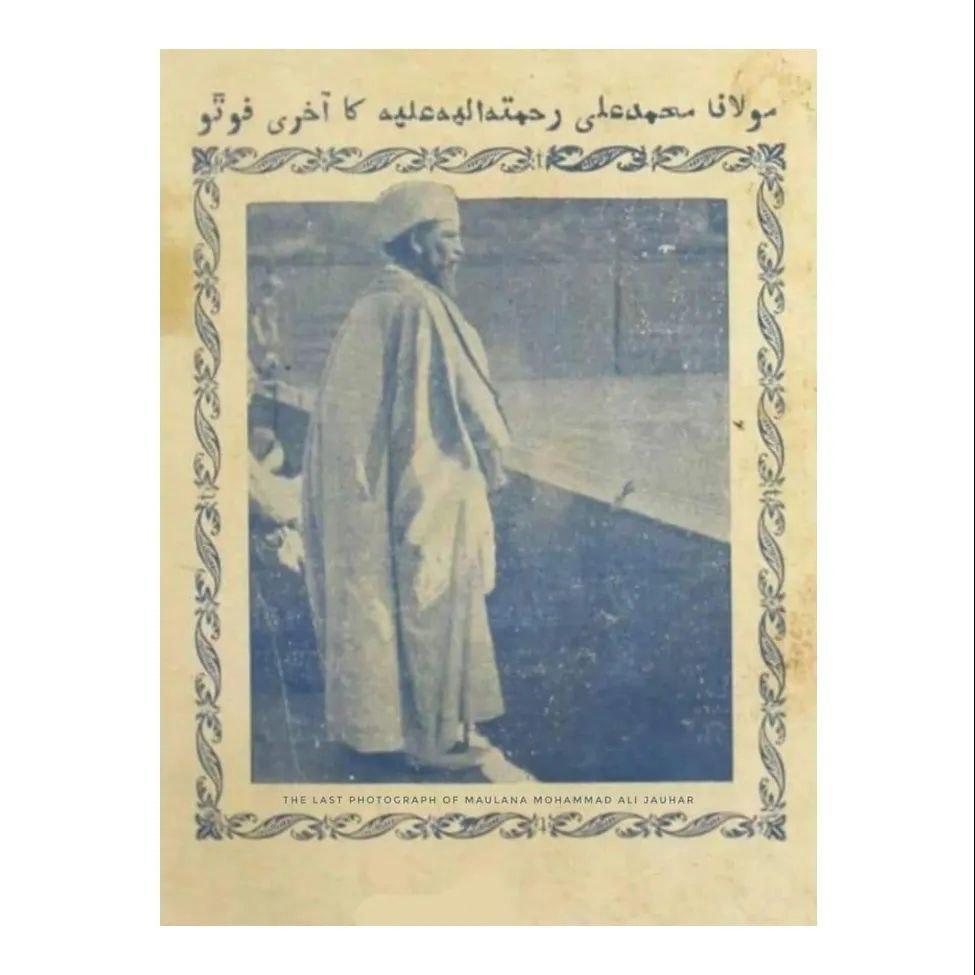

Moulana Mahomed Ali, before addressing the Jury, turning to the Court, said:

“Can I have the Jury on this side? I have not seen their faces yet. I want to seduce them like the troops.”

(Laughter in Court.)

The Court directed the Jurors to change their seats accordingly, and the Judge also changed the position of his seat, turning to the left, directly facing the accused.

Maulana Mohammed Ali then rose amid pin-drop silence, and addressing the Jury, said:

Gentlemen of the Jury,

I just asked the presiding Judge that he might permit me to see your faces because, with the exception of one of your number, I have not hitherto been able to see your faces. And I also said that I want to seduce the Jury. Of course, there was behind that another intention—not the ultimate object perhaps, but incidental to it, as the Public Prosecutor would say. I wanted you to act as a screen in front of the ladies now behind you, or the Public Prosecutor may add yet another charge of seduction against me.”

(Laughter.)

“But, after all, I find that as a result of my effort at seduction, I have turned the Judge also towards me today.”

(Laughter.)

“Gentlemen, I think I am going to take as much time as I can; so it is necessary to tell you beforehand that if I intended to defend myself or my friends and to escape from transportation for life or the gallows or the Jail—I don’t know what the Judge has in store for me—it would have been absolutely unpardonable.

No, Gentlemen, for that purpose I would not have wasted a single moment of your time or of mine.

I do not want any defence. I have no defence to offer. And there is no need of defence, for it is not we who are on trial. It is the Government itself that is on trial. It is the Judge himself who is on trial. It is the whole system of public prosecutions, the entire provisions of this law that are on trial.

It is not a question of my defence. It is a very clear issue and I thanked the Government in the lower court because for the first time it came out into the open and gave us a chance of having a decision on a very clear-cut and pointed issue.

That very clear-cut and pointed issue is this:

Is God’s Law for a British subject to be more important or the King’s law—a man’s law? Call him His Majesty or His Imperial Majesty, exalt him as much as you like—show all obedience to him—show him all the loyalty you can—pay him all the respect—entertain even superstitions about him if you like.

But the question is—is this respect, are these superstitions going to stand even for the slightest moment in the way of loyalty which every human being owes to God?”

Gentlemen, I think not for my own sake, nor for the sake of my co-accused, but I think for you. It is a misfortune that there is not a single Mussalman among you. Three of you are Christians and two are Hindus. But that does not matter at all. I am speaking to human beings; I am speaking mostly to Indians. I do not know whether all of you are Indians—perhaps one of you is not, though he too may have his domicile in India and may have come to regard India—although an Englishman as his home, —and may therefore be regarded as an Indian,

I am therefore speaking to a majority of you at least who came from a country which is imbued with the spirit of religion and which is traditionally a spiritual country and which has striven through ages for the exaltation of’ the spirit as against the flesh.

Toleration—What It Means?

Gentlemen, we hear so much of toleration in these enlightened days, and I do not think that even the Public Prosecutor would contradict me if I say that we all want toleration. The British Government has never tired of saying that it is a tolerant Government, and that British rule is firmly based on toleration.

I do not think that the Government of any civilized country in this twentieth century could ever say that it is against toleration. But what is toleration, after all? It is this, as a well-known man said:

“Sir, I disagree most heartily with every word of what you have said, but damn it, I shall fight to the last drop of my blood for your right to say it.”

That is toleration.

Toleration is required for disagreement; it is required where people are not of the same opinion, where people hold very different views—where there are wide differences. Otherwise, there is no necessity for toleration. But the tolerant man tolerates all this and sacrifices everything for the maintenance of tolerance.

Now, you might say, a man might hold very foolish opinions—I am sorry, many may do. I think the Public Prosecutor, for one, holds some very foolish opinions—and we have yet got to see what kind of opinion the Judge holds—that would be after I am silenced.

But it is not the question whether a man’s judgment is right or wrong. People’s judgment may be foolish.

The question is this: When any person or a body of persons gives you a pledge of freedom to hold your own opinions and act upon them, then I think it is their duty to abide by that pledge.

Now, Gentlemen, what is the case against us? We want the whole world to understand it. After all, the result of the decision here will not be confined to the audience in this hall or to the few scores of thousands of people in Karachi.

It was said that the Resolution that was passed here was not meant for that small body of the audience comprising a few Ulema and a few thousand people, but it was meant for a larger audience.

Now, this trial too is meant for more than the audience here in this hall—certainly for more than the five of you. It is really meant for the whole world.

We want to have our right to get the protection of the law for our religious beliefs and practices recognized.

Let the Government be repentant and say:

“We have seen the error of our ways.”

(Turning to Mr. Ross Alston)

These are the words which my friend Mr. Ross Alston wanted me to say as my last words, and they shall be my last words—but with regard to the action proper for the Government (laughter).

But will the Government say that? Is it going to abide by that pledge of freedom of Faith?

Or would the Government say:

“No, we are powerful, we are strong, we have dreadnoughts, we have aeroplanes, we have all this soldiery, we have machine guns, we have all this paraphernalia of destruction with us. We command tremendous power, we have beaten the most powerful nation in Europe—though of course with the help of twenty-six Allies (laughter) and India’s men, money, and other resources, but—that’s another story (laughter)—we cannot tolerate your religious opinions and acts.”

If they say that, we can understand that.

Therefore, it is not for the purpose of defending ourselves but to make this issue clear—because it is a national issue—nay, more than that—it is an issue on which the history of the world to a great extent depends.

Whether in this civilized century, man’s word shall be deemed higher than the word of God?

The trial is not “Mahomed Ali and six others versus the Crown,” but “God versus man.”

This case is, therefore, between God and man. That is the trial. The whole question is:

“Shall God dominate over man or shall man dominate over God?”

Skating Over Thin Ice

Now, Gentlemen, you were here—though it was not intended for you—you happened to be here—when we refused to stand up when the Judge asked us to do so.

We have always dissociated ourselves from and repudiated the idea of showing any disrespect to the Judge. We are not foolish enough to create any unnecessary unpleasantness or to worry the Judge or irritate him. We have no grudge against him.

But the whole question was with regard to respect for a man as against respect for God.

As my brother [Shaukat Ali] said in the lower court, and as I say before you now, we do not recognize the King any longer as our King—we do not owe any loyalty to any man who denies our right to be loyal to God.

I have not a word to say against the King—I have not a word against the Royal family. But where the question of God comes in as against the Government, I cannot have any respect for a Government when that Government demands from me that I must not first respect God and His laws.

Therefore, the whole question really is, as I have said, between God and man.

The Public Prosecutor has very skillfully stated his case, and when he came to our religious beliefs and the commandments of God, he was anxious to get over it as quickly as possible.

Was he skating over thin ice? He brushed all that aside.

Now, I challenge him—I challenge the Judge—to give a decision on the point.

It is not at all a question of facts with which you, gentlemen of the Jury, have to deal. If the Judge deals with the question of law in his summing up, and sentences us—if the verdict of the Jury goes against us in the case in which you act as Jurors—and if he exercises his right as a Judge to decide both as regards the facts and the law in the cases in which you act merely as assessors, after you give your opinion as assessors—then our course will be clear.

If the Judge sentences us, disregarding our religious obligations, then it does not matter what punishment we are likely to get and under what section of the Penal Code we get it.

There are any number of sections—sections 120-B, 131, 109, 505, 117, and so on.

As regards those sections and the various charges, so far as I am concerned, I was greatly confused, and I am trying to compute how many years altogether I shall get (laughter).

I have but one life, and I do not know if it can cover the many years that I shall get if I am punished according to my deserts (laughter).

But that is absolutely immaterial.

(To be continued)