Hinduism and India’s Conduct of Conventional Warfare

On 9 May 1929, M. K. Gandhi declared:

This I know that if India comes to her own demonstrably through non-violent means, India will never want to carry a vast army, an equally grand navy and a grander air force. If her self-consciousness rises to the height necessary to give her a non-violent victory in her fight for freedom, the world values will have changed and most of the paraphernalia of war would be found to be useless.22

While Gandhi advocated abolishing the armed forces in free India, Nehru demurred. The latter may not have been interested in matters military but did not completely neglect them. In 1937, Nehru noted:

There is no doubt that India can build up an efficient defense apparatus…. We live in an abnormal world, full of wars and aggression, when international law has ceased to be and treaties and undertakings have no value, and an unabashed gangsterism prevails among nations…. The only thing to be done to protect oneself is to rely on one’s strength as well as to have a policy of peace.23

Despite the Nehruvian policy of apathy as regards projection of power overseas, India has been very sensitive as far its borders are concerned and has not hesitated to start conventional operations when its borders have been threatened. Tanham offers an explanation:

Independent India sees itself as continuing the tradition of non-aggression and non-expansion outside the subcontinent. Nehru’s foreign policy rested on these principles, and subsequent leaders have followed suit. The tradition of non-aggression, however, has never applied internally. Warfare within the subcontinent has been the norm for centuries. States fought to gain power and wealth, to establish empires, or to destroy them. This seeming paradox with regard to non-aggression arises from the Indian view of the subcontinent as a single strategic area that coincides with Indian national interests. This belief justified India’s taking much more aggressive measures – to protect its interest in the subcontinent.24

Air Marshal R. K. Nehra asserts that post-1947 India’s military response to its hostile neighbors like Pakistan and China has been passive owing to the pervasive influence of the Hindu mindset. Too much focus on ahimsa and shanti (peace) is seen by Nehru as the root cause of India’s fragmented approach to matters military. The focus on non-violence in Hinduism, argues Nehra, is due to the pervasive influence of Buddhism. In original Hinduism, martial valor was emphasized. Nehra cites the sloka: ‘Vira bhoga Vasundhara’, that is, the mighty heroes will enjoy the earth.25 In a similar vein, Brigadier Kuldip Singh notes, in a monograph published in 2011, that ancient Hinduism emphasized just militarism. He continues:

India’s military mind is as pristine, resplendent and advanced as its longstanding civilization. Its inherent philosophy of life and statecraft accorded exalted primacy to warfare, as evident from the vedas, the epics, Arthasastra and other classics…. Indians were not only men of thought alone, but men of action too. The aggressive combative spirit of ancient Bharata is exemplified by its confederated military might, which evicted the Greeks, Kushan and Hun invaders from the Indian soil.26

The retired Indian Lieutenant-General S. C. Sardeshpande writes that India’s passive defense policy throughout its history is a product of the ‘inward looking self-satisfied attitude’ of the people. This is due in part to the geographical features of India. High mountains in the north and jungle filled hills in the east, with sea and ocean along the western and southern borders, has resulted in India being an ‘inward-looking geographical entity.’ Hence, the people are satisfied with their natural geographical frontiers. Throughout history, Indians have not exhibited any extra-territorial ambitions.27 This geographical inwardness has been further strengthened by cultural passivity. Sardeshpande notes: ‘Preoccupation with spiritualism, theorizing, complacency and plentitude led Indian militarism away from geographical planes to the peculiar planes of glory, honor, sport and kind of ritual.’28 The net result throughout history has been a sort of non-lethal warfare. He continues: ‘But perhaps because of cultural identity and stress on spiritualism, wars seldom attained cruel, fanatic or exterminatory proportions. By and large wars remained far less inhuman as compared to those in European and American continents.’29

As regards Indian politicians’ attitude towards the armed forces, Nehra comments: ‘… the new rulers of the country suffered from an overdose of ahimsa, which has become a part of their mental make-up; it was lodged in their subconscious. Most of them felt apologetic about militarism. There was a visible lack of enthusiasm about the armed forces in the political class.’30 For instance, in 1955, Nehru declared that India’s symbols throughout its long history had never been great military commanders but men like Buddha and, in our own time, Gandhi, both of whom were messengers of goodwill and peace.31 Kuldip Singh warns politicians about the importance of military strength for national security in the following words: ‘India’s inherent depth and vitality of dharma, spirituality and wealth of knowledge and natural resources, on their own, could not protect its frontiers. The case of Emperor Asoka bears out how India’s neglected defense system led to national humbling and foreign intrusion, in spite of its otherwise established civilizational grandeur during his time.’32

Because politicians have neglected defense since Independence, claim several military officers, the armed forces have become demoralized. The performance of the Indian army during the 1965 war with Pakistan was below average owing to a defensive mindset and a lack of an aggressive attitude and killer spirit. Nehra gives an instance of the defeatist Hindu mindset prevailing even among the top officers of the armed forces. In 2009, Admiral Suresh Mehta, the chief of the naval staff and chairman of the Chiefs of Staff Committee, publicly stated that India could never catch up with China and that the gap between the two would only widen with time.33 Kuldip Singh warns: ‘We need to change the attitude and recognize that war undertaken for a noble cause, and as the last resort, it is the highest worship of God.’34

(Photo credit: By Abhinayrathore at English Wikipedia – Work of Brig. Hari Singh Deora A.V.S.M, Public Domain, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=23514297)

Both civilian commentators and military officers suggest that the epics could impart lessons for the modern military. For instance, Waheguru Pal Singh Sidhu claims that the Mahabharata highlights the strategy for breaking into and breaking out of a chakravyu (enemy encirclement).35 Brigadier G. D. Bakshi writes that principles of war could be gleaned from the Mahabharata. Despite changes in technology, the tactical and strategic principles of warfare remain constant. He comments that the Mahabharata War was a high-intensity war of short duration; it lasted for only eighteen days. All the conventional wars fought by India with Pakistan and China were also of short duration. For instance, the Second India-Pakistan War (1965) lasted for twenty-two days, and the Third India-Pakistan War (1971) lasted for fourteen days. Again, the Mahabharata notes that the campaigning season lasts from November to March. Bakshi notes that independent India’s wars, like the 1962 China-India War, occurred during November-December. Later, the 1971 India-Pakistan War occurred during November and December. The Mahabharata emphasizes that wars are to be fought with large numbers of regular soldiers, and the Indian army is comprised of long-service volunteer soldiers from the ‘martial races’.36

Bakshi notes that in the Mahabharata one finds two military approaches: the traditional direct approach, enunciated by Bhisma, and the indirect approach as practiced by Lord Krishna and Dronacharya’s son Ashwathama. The latter approach finds its logical culmination in Kautilya’s kutayuddha. The former approach dominates the Indian military mind. The direct approach of conducting dharmayuddha – emphasizing restraint, chivalry, a sporting mentality, symmetrical responses, and so on – is responsible for the inefficiency of Indian tactics. Bakshi continues that in accordance with the dharmayuddha tradition, Indian armour was used during the India-Pakistan conflicts only against enemy armor in a tank-killer role. Indian armor was not used against enemy infantry or for deep penetration of the enemy’s vulnerable flanks due to the ethics of dharmayuddha. 37 For instance, during the 1965 India-Pakistan War, an Indian armored division was ordered to seek out and engage Pakistan’s First Armored Division in a classic tank-versus-tank battle. It was an attrition-oriented paradigm, and the Indian generalship was further hamstrung by over-cautiousness and rigidity.38 It is part of our inheritance, Bakshi continues, that chariots must only attack chariots.39 Here, Bakshi is referring to the Mahabharata and Manusamhita’s concept of dharmayudha.

After analyzing the three India-Pakistan Wars, Bakshi notes in an article:

By historical legacy, we are an attrition-oriented army. This legacy goes back to the era of the Mahabharata War in 1200 BC. Today, we need to grow beyond tactical frontal pushes at the corps level. Our Operational Art must be enhanced in sophistication to include single and double envelopment pincer movements and turning movements…. What we need to recognize is the … level of Operational Art in the context of limited or unlimited wars in the subcontinent and the dire necessity of outgrowing attrition mindset (which incidentally is a legacy of the Mahabharat War).40

In Bakshi’s eyes, the absence of intelligence-oriented covert operations is a weakness of the Indian military system. He writes:

Kutayuddha methods were despised by ‘honorable’ Indian soldiers of the Mahabharata period. The tragedy is that even today our Indian regular soldiers still tend to despise these methods as unethical or unsoldierly. Notice the fact that officers of our intelligence corps have no bright career opportunities vis-à-vis the other arms. It appears intelligence and covert operations are second rate side shows for which only second grade officers can or need be spared. This attitude has been further reinforced by our British heritage.41

Bakshi’s observation is supported by a fellow officer, Kuldip Singh, in the following words: ‘The poor showing of India’s intelligence system has been an interminable story of unmitigated disaster. The importance of having an effective intelligence organization is highlighted in not only the epics, but also the Arthashastra constitutes an ageless masterpiece on surveillance and spying, in both peace and war.’42 Bakshi claims that the acharyas of the Mahabharata were experts in conducting psychological war. Their main aim at all times was to attack the mind of the enemy commander.43

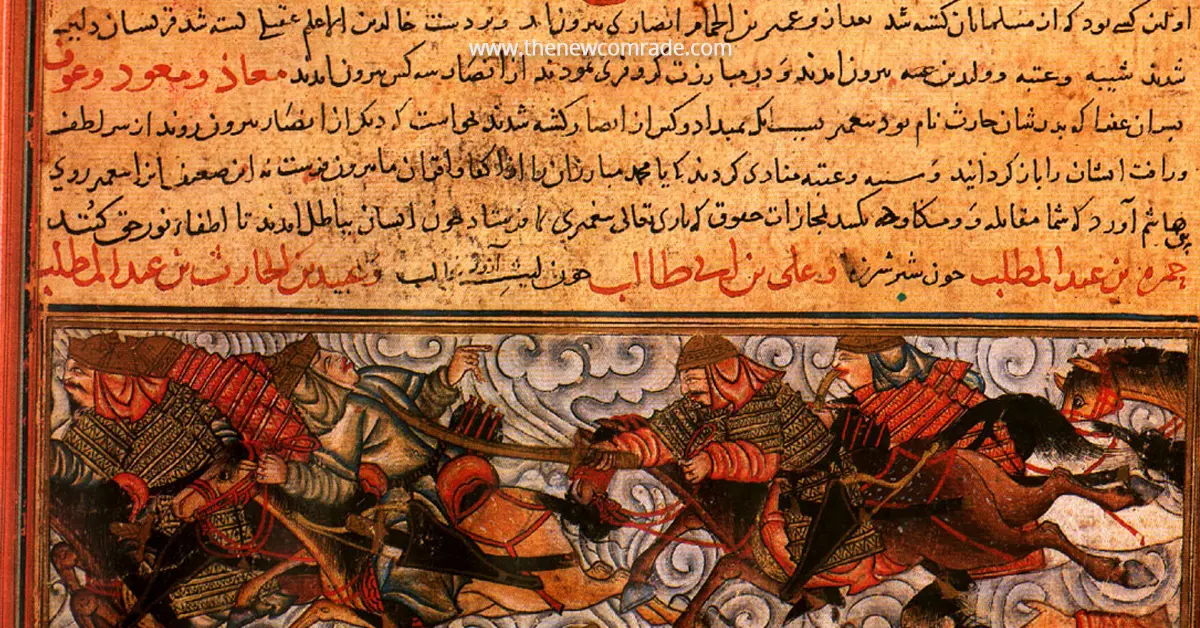

If necessary on the basis of historical study, certain aspects of Hinduism, write some officers, need to be revised. Kuldip Singh concludes that the failure of the Hindus during the medieval era was due to passive defence. The medieval Hindu rulers failed to pre-empt Islamic invasions and also did not carry the battle to the invaders’ bases. Hence, all the battles were fought deep inside India. Singh is probably referring to Prithviraja Chauhan and the two battles of Tarain with Muhammad Ghori. Aggressive defence and pre-emptive action could have saved the Hindus. And, Kuldip Singh emphasizes, we should learn from such mistakes.44

C. Coker claims that the principal lesson of Arthasastra is asymmetric warfare. In 1988, the office of the U.S. secretary of defence concluded that India would seek to deny the U.S. Navy uncontested control over the Indian Ocean and that New Delhi would use asymmetric sufficiency as a counter. In Indian coastal warfare, subsurface weapons could function as a deterrent.45

This article is a republished version of chapter 7 from the author’s work titled ‘Hinduism and the ethics of warfare in south Asia‘)

Bibliography

22 The Essential Writings of Mahatma Gandhi, ed. by Raghavan Iyer (1993; reprint, New Delhi: Oxford University Press, 2007) (hereinafter EWMG), p. 275.

23 EWJN, vol. 1, p. 41.

24 Tanham, ‘Indian Strategic Thought’, p. 77.

25 Air Marshal R. K. Nehra, Hinduism and Its Military Ethos (New Delhi: Lancer, 2010), p. 325.

26 Brigadier K. Kuldip Singh, Indian Military Thought: Kurukshetra to Kargil and Future Perspectives (New Delhi: Lancer, 2011), p. 592.

27 Lieutenant-General S. C. Sardeshpande, War and Soldiering (New Delhi: Lancer, 1993), p. 126.

28 Ibid., p. 127.

29 Ibid.

30 Nehra, Hinduism and Its Military Ethos, p. 329.

31 EWJN, vol. 2, p. 289.

32 Singh, Indian Military Thought, p. 593.

33 Nehra, Hinduism and Its Military Ethos, pp. 331, 337, 351.

34 Singh, Indian Military Thought, p. 599.

35 Sidhu, ‘Of Oral Traditions and Ethnocentric Judgements’, p. 175.

36 Lieutenant-Colonel G. D. Bakshi, Mahabharata: A Military Analysis (New Delhi: Lancer, 1990), pp. 72–3.

37 Bakshi, Mahabharata: A Military Analysis, pp. 73–4.

38 G. D. Bakshi, ‘Operational Art in the Indian Context: An Open Sources Analysis’, Strategic Analysis, vol. 25, no. 6 (2001), p. 728.

39 Bakshi, Mahabharata: A Military Analysis, p. 74.

40 Bakshi, ‘Operational Art in the Indian Context’, pp. 732–3.

41 Bakshi, Mahabharata: A Military Analysis, p. 74.

42 Singh, Indian Military Thought, p. 593.

43 Bakshi, Mahabharata: A Military Analysis, pp. 74–5.

44 Singh, Indian Military Thought, pp. 593–4.

45 Christopher Coker, Waging War without Warriors? The Changing Culture of Military Conflict (Boulder, Colorado: Lynne Rienner, 2002), pp. 142–3.