With the British departure from India in 1947, British India was partitioned into India and Pakistan. Though India officially claims to be a secular state, Hinduism continues to influence statecraft. At the beginning of the new millennium, India is a rising power, if not a mini-superpower. India’s economy is growing at an annual rate of 6 percent, and it is the fourth-largest economy, after the United States, China and the European Union.1 India’s land frontiers exceed 15,000 km, and it shares land frontiers with seven countries. India’s coastline is 7,600 km long, and its exclusive economic zone is over two million square km. The island territories in the east are 1,300 km away from the mainland. India shares a maritime boundary with five countries.2

And the Indian army, with more than a million men, is the fourth-largest in the world. This chapter shows the influence of the Hindu ethos in four areas: grand strategy, conventional warfare, unconventional warfare and the nuclear issue.

Hinduism and India’s Grand Strategy

Jawaharlal Nehru (1889–1964, independent India’s first prime minister 1947–64) believed in the civilizational inheritance of India. He wrote: ‘There seemed to me something unique about the continuity of a cultural tradition through five thousand years of history, of invasion and upheaval, a tradition which was widespread among the masses and powerfully influenced them. Only China had such a continuity of tradition and cultural life.’3 However, he did not overlook differences in India. Rather, he emphasized, ‘cultural unity amidst diversity’.4 Nehru continues: ‘… a country with a long cultural background and a common outlook on life develops a spirit that is peculiar to it and that it impressed on all its children, however much they differ among themselves.’5 Here Nehru is expressing something similar to the approach of the strategic culture theorists.

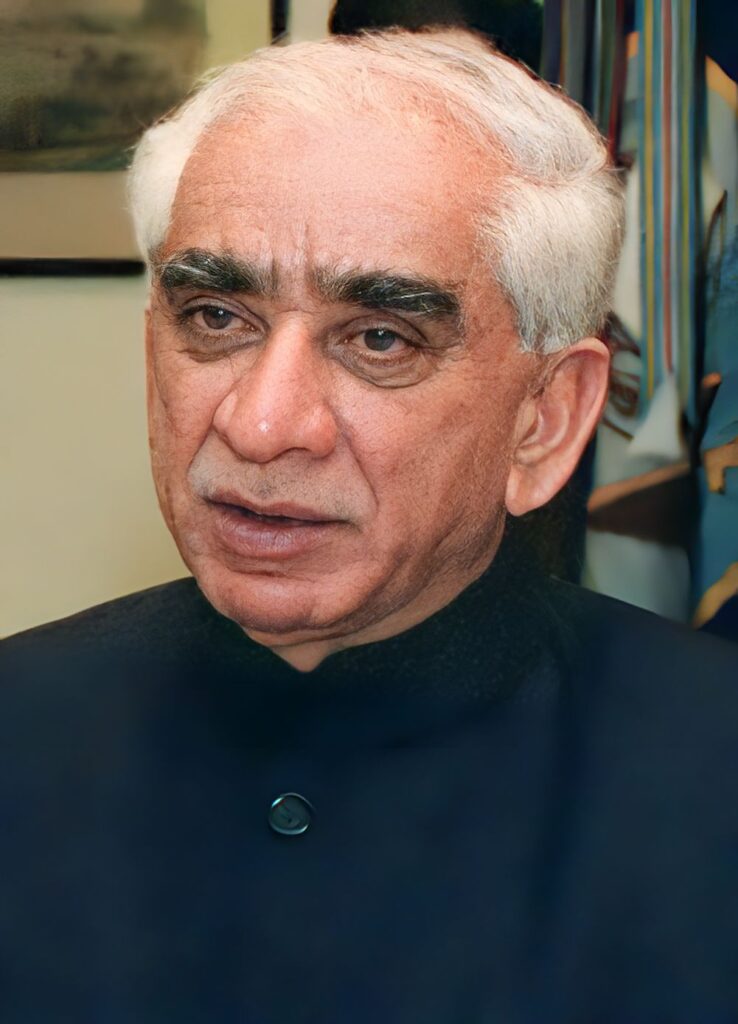

However, Nehru differs from the strategic culture theorists when, unlike the latter, he assumes that the civilizational ethos of Bharat is not confined to a mere handful of elites but has imbued even the common masses through the ages. Nehru noted: ‘… for our ancient epics and myths and legends, which they knew so well, had made them familiar with the conception of their country, and there were always some who had travelled far and wide to the great places of pilgrimage situated at the four corners of India.’6 Nehru is not alone in identifying a civilizational ethos of India. Jaswant Singh, who served as deputy chairman of the Planning Commission and also as foreign minister in the Bharatiya Janata Party (i.e., the BJP, the Hindu right-wing party of independent India) government (1998–2004), like Nehru and Gandhi accepted the idea that the accommodating capacity is one of the principal characteristics of Hinduism. The strength of India’s civilization, in Nehru’s paradigm, lies in its capacity to adapt and assimilate.7 In Jaswant Singh’s words: ‘Sanatan is “for all”; it is the ultimate of inclusiveness, it is sanatan that subscribes to the noble concept of “sarvapath sambhav”.’8 Singh asserts that India is accommodative and tolerant because of Hinduism. Unlike the case of countries with Judaic religions, in India other religions have flourished. In Jaswant Singh’s paradigm, unlike that of Nehru, the Hindu influence is grossly represented. Jaswant Singh claims that there is only one culture in India. It is Indian/Hindu/Bharatiya.9

Jaswant Singh notes the negative effect of Hinduism on India’s grand strategy:

The ethos of the Indian state was crippled by another failing. Not just occasional, often an excessive, and at times ersatz pacifism, both internal and external, has twisted India’s strategic culture into all kinds of absurdities. Many influences have contributed to this: an accommodative and forgiving Hindu milieu; successive Jain, Buddhist, and later Vaishnav-Bhakti influences resulting in excessive piety and, much later, in the twentieth century ahimsa…. An unintended consequence of all these influences, spread over many centuries, has been a near total emasculation of the concept of state power, also its proper employment as an instrument of state policy, in service of national interests.10

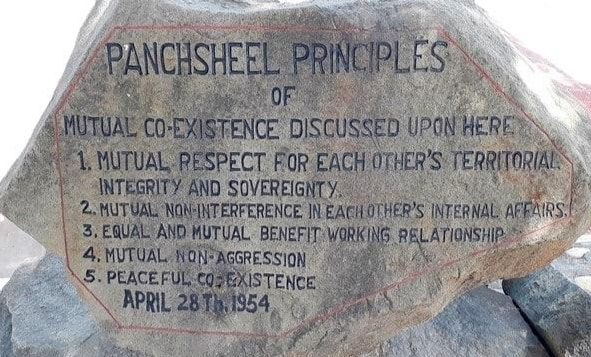

The core concept of Nehru’s foreign policy was the Panchsheel (five principles), which Nehru explained to the Lok Sabha (the Lower House of the Parliament) on 17 September 1955. The first principle is recognition by countries of their own and each other’s independence, sovereignty and territorial integrity. The second is non-aggression; the third is non-interference with each other; the fourth is mutual respect and equality; and the fifth is peaceful coexistence.11 Jaswant Singh judges Nehru’s Aussenpolitik harshly. He writes that the core of Nehru’s position on China, ‘Hindi-Chini Bai Bhai’ and ‘Panchsheel’, perished on the bleak heights of the Aksai Chin and the high passes of north-east India in the late autumn of 1962. And these two significant foreign policy errors were the direct outcome of Nehru’s idealistic romanticism.12

One modern Indian analyst notes that even the policy of ahimsa followed by Gandhi, which to an extent influenced Nehru, has elements of realism inherent in it. He justifies Nehru’s ‘peaceful’ policy towards China through the lens of realism. He claims that in the 1950s, the Indian army was going through a process of reorganization. At that time, it was no match for the People’s Liberation Army of China. Hence, Nehru had recourse to Panchsheel. 13 Despite the rhetoric, Nehru also tried to attain a hegemonic position for India. As early as 1948, Nehru wrote that India is the natural leader of Southeast Asia, and perhaps of some other parts of Asia as well. This is because there was no other possible leadership in Asia, and any foreign leadership would not be tolerated.14 Under Nehru’s stewardship, when India tried to follow such a course, it resulted in conflict with China.

When necessary, Nehru was not averse to utilizing Kautilya’s dictum: ‘my enemy’s enemy is my friend’. Just one year after independence, Nehru observed:

… as a result of Pakistan coming into existence and the growth of an Islamic sentiment, the Middle Eastern countries will tend to become somewhat hostile to India…. Our general policy in regard to them should be one of friendship as well as firmness…. Afghanistan being anti-Pakistan, automatically is a little more friendly to India. We should take full advantage of this fact. Turkey also is not very much affected by the Islamic sentiment.15

Tension between Afghanistan and Pakistan over the Durand line, in Nehru’s eyes, was to be used as diplomatic leverage by India. Another streak of Nehru’s realism is evident in the letter of advice he wrote to U. Nu of Burma in 1949. Nehru wrote that any attempt to fight on all fronts is not likely to succeed and may well end in serious losses. In politics as in warfare, Nehru advised U. Nu, one takes up one’s enemies one by one.16

C. Raja Mohan, an Indian foreign policy analyst, offers a realist interpretation of Nehru’s non-aligned movement. India’s treaty-based relations with Nepal and Bhutan were security alliances whereby New Delhi promised to protect these states against external threats. This constituted India’s inner circle. In the next concentric circle, which comprised India’s extended neighborhood, New Delhi’s policy was determined more by balance-of-power considerations than by ideological ones. India refused to join the non-aligned bandwagon against the Soviet Union’s intervention in Afghanistan in the early 1980s. This is because from the 1970s onwards the USSR had been India’s steadfast ally. At the global level, the third concentric circle, India’s alignment with the Soviet Union was shaped by considerations of national interest. Throughout the Cold War, India determinedly sought to reduce Chinese influence in Southeast Asia. There is nothing, then, in the history of India’s non-aligned policy that suggests a fundamental aversion to playing power politics, including alliances.17 Both Raja Mohan and George K. Tanham (an American analyst) accept the idea that Kautilya’s mandala policy continues to shape India’s grand strategy.18

In the last decade of the twentieth century, India’s strategic policy represented both change and continuity. The imperatives for change were the disappearance of the USSR and the fiscal crisis that led the Narasimha Rao–led INC government in the 1990s to start the process of globalization.19 Tanham, taking a leaf from Samuel Huntington’s clash of civilizations scenario, portrays India’s strategic landscape in the following words:

India continues to see Islam as a … threat. Having been invaded by different Muslim peoples for several centuries, then ruled by the Mughals for about 200 years, Indians are understandably sensitive to perceived Islamic threats. Today, they are surrounded on their land borders by seven Muslim countries. Pakistan’s destabilizing efforts in India, supported by other Muslim nations is the clearest and nearest and most important Islamic threat. The recent formation of five independent republics in Central Asia, all with large Muslim populations, is seen as the latest manifestation of the Muslim presence.20

Even with potentially hostile neighbors, India’s policy is to seek cooperation first, if possible, with some, if not with all; the last option is war. Swarna Rajagopalan asserts that India’s policy of seeking strategic cooperation with its neighbors is shaped by the ethical security politics derived from the Ramayana. One of the principle themes of the Ramayana is strategic cooperation for the purpose of tackling the enemy. This is evident in Rama’s strategic alliance with the vanaras for the purpose of tackling Ravana.21

(This article is a republished version of chapter 7 from the author’s work titled ‘Hinduism and the ethics of warfare in south Asia‘)

Bibliography

1 Bharat Karnad, Nuclear Weapons and Indian Security: The Realist Foundations of Strategy (New Delhi: Macmillan, 2002), p. xx.

2 Ministry of Defence Government of India Annual Report (hereinafter MODAR), 2000– 2001, p. 2.

3 The Essential Writings of Jawaharlal Nehru, ed. by S. Gopal and Uma Iyengar, 2 vols. (New Delhi: Oxford University Press, 2003) (hereinafter EWJN), vol. 1, p. 5.

4 EWJN, vol. 1, p. 22.

5 Ibid., p. 7.

6 Ibid., p. 8.

7 Ibid., p. 34.

8 Jaswant Singh, A Call to Honour: In Service of Emergent India (New Delhi: Rupa, 2006), p. 87.

9 Singh, A Call to Honour, pp. 88–9.

10 Jaswant Singh, Defending India (Houndmills, Basingstoke: Macmillan, 1999), p. 13.

11 EWJN, vol. 2, p. 163.

12 Singh, Defending India, p. 34.

13 Waheguru Pal Singh Sidhu, ‘Of Oral Judgements and Ethnocentric Judgements’, in Kanti P. Bajpai and Amitabh Mattoo (eds.), Securing India, Strategic Thought and Practice: Essays by George K. Tanham with Commentaries (New Delhi: Manohar, 2006), pp. 176–7.

14 EWJN, vol. 2, p. 237.

15 Ibid., pp. 237–8.

16 Ibid., p. 251.

17 C. Raja Mohan, Impossible Allies: Nuclear India, United States and the Global Order (New Delhi: India Research Press, 2006), pp. 267–8.

18 George K. Tanham, ‘Indian Strategic Thought: An Interpretive Essay’, in Bajpai and Mattoo (eds.), Essays by George K. Tanham with Commentaries, pp. 47–72.

19 George K. Tanham, ‘Indian Strategy in Flux?’, in Bajpai and Mattoo (eds.), Essays by George K. Tanham with Commentaries, pp. 113–15, 134.

20 Ibid., p. 129.

21 Swarna Rajagopalan, ‘Security Ideas in the Valmiki Ramayana’, in Rajagopalan (ed.), Security and South Asia: Ideas, Institutions and Initiatives (London/New York/New Delhi: Routledge, 2006), pp. 24–53.