Clausewitz and Kautilya

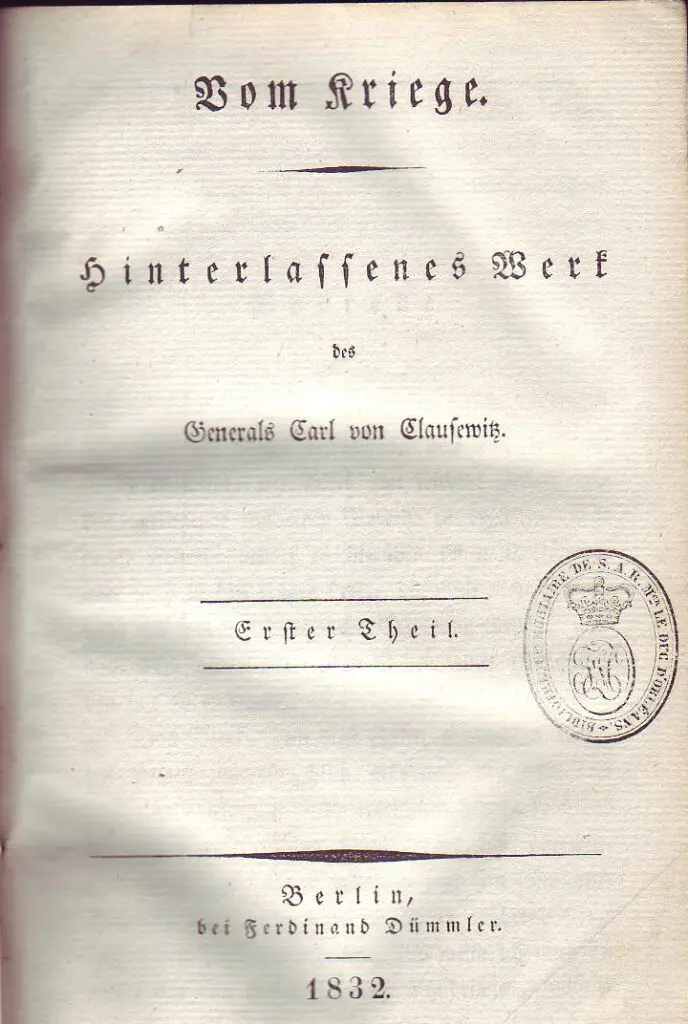

On War, or Vom Kriege, was first published in three volumes in Berlin between 1832 and 1834. Its author, Carl Philipp Gottlieb von Clausewitz, was born on 1 June 1780, at Burg, near Magdeburg. His grandfather was a professor of theology, and he was a Lutheran pastor. Clausewitz made little reference to religion in his own writings. He did not cite faith as a motivation for war. Nor did he view Christianity as an impulse for moderation when fighting fellow Christians.113 Clausewitz was a soldier from the age of twelve until his death in 1831. He started working on On War after 1815.114 In a note written around 1818, Clausewitz comments: ‘My original intention was to set down my conclusions on the principal elements of this topic in short, precise, compact statements, without concern for system or formal connection. The manner in which Montesquieu dealt with his subject was vaguely in my mind.’115 In 1827, Clausewitz started to revise his work, but the task remained unfinished due to his early death.116

Clausewitz implies that transformation in politics results in transformation of warfare. Clausewitz’s famous statement follows: ‘War is nothing but the continuation of policy with other means.’117 He clarifies: ‘The political object is the goal, war is the means of reaching it, and means can never be considered in isolation from their purpose.’118 On War says that ‘the political aim remains the first consideration. Policy, then, will permeate all military operations, and, in so far as their violent nature will admit, it will have a continuous influence on them.’119 Clausewitz’s trinity comprises of people and their passion, the commander and his army and the nature of the government.120 Clausewitz claims that ‘the political aims are the business of government alone.’121 Clausewitz emphasizes the supremacy of politicians over military commanders when formulating grand strategy.122 In Kautilya’s theory, the vijigishu completely overshadows the senapati.

Clausewitz, like Kautilya, sees warfare as instrumental. The conduct of war needs to reflect the fact that its objective is the establishment of peace.123 Kautilya differs from the position of the Bhagavad Gita, where the purpose of war is existential. Both Clausewitz and Kautilya are realists and assume that inter-state war is necessary and inevitable in the highly competitive and harsh international arena.124 And along with Clausewitz, Johann Jakob Otto August Ruhle von Lillienstern also argued that war fulfilled a political purpose. By 1804, Clausewitz had read Machiavelli’s Discourses (begun in 1513). Clausewitz admired Machiavelli’s emphasis on the realities of power and probably learnt from him that war has a political purpose.125 P. C. Chakravarti writes that Kautilya, like Clausewitz, believed that war is the continuation of politics by other means.126

Clausewitz writes: ‘War is thus an act of force to compel our enemy to do our will.’127 As regards the means of war, he notes:

There is only one: combat. However, many forms combat takes, however far it may be removed from the brute discharge of hatred and enmity of a physical encounter, however many forces may intrude which themselves are not part of fighting, it is inherent in the very concept of war that everything that occurs must originally derive from combat…. Warfare comprises everything related to the fighting forces – everything to do with their creation, maintenance, and use…. The end for which a soldier is recruited, clothed, armed, and trained, the whole object of his sleeping, eating, drinking, and marching is simply that he should fight at the right place and the right time. 128

Clausewitz dismissed Adam Heinrich Dietrich von Bulow’s (1757–1807) assertion that it is always possible to avoid battle.129 Clausewitz introduces the concept of the centre of gravity (schwerpunkt), which constitutes the hub of all power and movement of the enemy.130 Clausewitz’s concept of centre of gravity is taken from Newton’s law of mechanics.131 In the case of world conquerors like Alexander, Gustavus Adolphus, Charles XII and Frederick the Great (equivalent to Kautilya’s vijigishu), the centre of gravity was their army.132

As regards the object of combat, Clausewitz hammers the point that ‘of all the possible aims in war, the destruction of the enemy’s armed forces always appear as the highest.’133 In a note written in 1830, Clausewitz emphasized that ‘victory consists not only in the occupation of the battlefield, but in the destruction of the enemy’s physical and psychic forces, which is usually not attained until the enemy is pursued after a victorious battle.’134 Clausewitz writes: ‘The invention of gunpowder and the constant improvement of firearms are enough in themselves to show that the advance of civilization has done nothing practical to alter or deflect the impulse to destroy the enemy, which is central to the very idea of war.’135 He writes that in war maximum effort must be made by simultaneous concentration of forces to obtain the first decisive victory.136 Clausewitz claims that even when a state is on the strategic defensive, it should launch a tactical offensive.137 Kautilya opposes the waging of a tactical offensive by the vijigishu when the strategic picture is becoming less favourable to him. Kautilya writes that in such a scenario tactical offensives become useless, using the expression ‘entering the flame like a moth’.138 Rather, in such circumstances, Kautilya advocates following a policy of ‘wait and watch’. Both Kautilya and Clausewitz emphasize the role of reserve in the battlefield.139

Machiavelli emphasizes the importance of battle in warfare.140 In Clausewitz’s On War and also for Thucydides, bloodshed constitutes the most important characteristic of warfare. The Arthasastra, influenced by ancient India’s military experiences, marginalizes the role of battle in warfare. Around 530 BCE, Cyrus, the Achaemenid emperor of Persia, crossed the Hindu Kush and occupied Gandhara. In 518 BCE, Darius I, the Achaemenid monarch, annexed Punjab, which became the twentieth satrapy (province) of his empire.141

The greatest battle fought in ancient India, the Battle of Hydaspes (326 BCE), influenced Kautilya’s thought as regards the tactical aspects of warfare and his ideas about military organization. Initially, Paurava dispatched 2,000 cavalry and 120 chariots under his son to oppose Alexander’s crossing of Jhelum. Alexander defeated this contingent, and then Paurava advanced with his main force to check Alexander.142 In this battle, Paurava deployed 200 elephants and 30,000 infantry, 4,000 cavalry and 300 chariots.143 Compared to the vedic and epic chariots, Paurava’s chariots were larger. Ajatasatru introduced scythe chariots into the Magadhan army.144 The Macedonian heavy infantry made short work of the chariots, as in Gaugemela. Paurava placed 2,000 cavalry at each of the wings. Alexander ordered Coenus with his cavalry to attack the cavalry on Paurava’s right wing. As Coenus moved towards Paurava’s right wing, Alexander was proceeding towards Paurava’s left wing. Meanwhile, Paurava ordered the cavalry on the right wing to come to the support of his outnumbered left wing. Then Alexander ordered his horse archers to attack the Indian left wing. When the Indian cavalry concentrated on their left wing, Coenus appeared at their rear. As part of the Indian force turned around to meet Coenus, Alexander delivered his attack. As in Gaugemela, the Macedonian cavalry attacked in a wedge formation. Then the elephants advanced towards the Greek cavalry. After a furious struggle, the elephants were overwhelmed by Greek phalangites and 1,000 mounted archers that Alexander had bought from Central Asia.145

After 400 BCE, chariots were no longer used in China.146 Despite the uselessness of the chariots in the Battle of Hydaspes, Kautilya writes about the necessity of chariots in the battle order of the vijigishu, and the Maurya army-maintained chariots.147 This was because disciplined infantry and good horses were not available to the Mauryas. The elephants impressed the Greeks, and the use of war elephants spread in the Western world. Pyrrhus, the king of Epirus, used elephants at Heraclea (280 BCE).148 The Nandas maintained 80,000 cavalry, 200,000 infantry, 8,000 chariots and 6,000 elephants. Chandragupta raised the number of infantries to 600,000 and the elephant corps to 9,000, but his cavalry numbered only 30,000. In other words, the Maurya cavalry was numerically weaker than the Nanda cavalry establishment.149 This was despite the fact that at the climactic Battle of Hydaspes, it was Alexander’s cavalry that played the crucial role. Kautilya notes that good horses were available only outside India, at Kamboja (north of Gandhara, i.e., Afghanistan) and Vanayu (Arabia or Persia).150 The contemporary Chinese emperors were also interested in having war horses. Around 100 BCE, the Han Emperor Wu-ti/di (140–87 BCE) directed several campaigns against Ferghana (in Russian Turkestan) to acquire horses. The horses from Ferghana were also used for breeding a better variety of horses that was required for fighting the nomadic invaders.151 The Mahabharata mentions the presence of mounted archers with composite bows. Neither Paurava nor Chandragupta possessed mounted archers. In fact, Kautilya never mentions the presence of mounted archers in the vijigishu’s order of battle. The invading Aryans probably introduced mounted archery on the subcontinent, but this practice died out.152

D. D. Kosambi claims that due to a shortage of metals, most of the Indian soldiers who opposed Alexander could not afford metallic body armour. The bulk of the soldiers, in his views, were equipped with a shield, a leather cuirass and a metal helmet.153 Herodotus tells us that the Indian bowmen in Xerxes’ army used bows made of cane and bamboo.154 The Indian bowmen at Hydaspes were foot archers and used arrows, each of whose shaft was three yards long.155 The arrow was discharged with the pressure of the archer’s left foot on the extremity of the bow, which rested on the ground, and the string was drawn far backwards. Such arrows were able to penetrate shields and breastplates.156 Due to rainfall on the night before the battle, the ground was slippery, and the Indian archers failed to make effective use of their bows in the decisive conflict at Hydaspes.157 Kautilya was for retaining the foot soldiers and especially the archers, but tried to raise their combat effectiveness through training.

A close reading of the Arthasastra challenges the observation of some modern historians that ancient India lacked a disciplined standing army. The Arthasastra tells us that an army is organized in squads of 10 men, companies of 100, and battalions of 1,000 each.158 Kautilya says that the nayaka (warlord) with trumpets and flags should coordinate the movement of the various units of the army on the battlefield.159 For fighting prakasya yuddha, Kautilya urges the vijigishu to deploy troops in well-ordered vyuhas. Various types of vyuhas are described in the Arthasastra, depending on the terrain and the force structure. Each vyuha was comprised of five sections: a centre and two flanks that were further protected by two wings. Each section was comprised of combined battle units (infantry, cavalry, elephants and chariots).160 At Hydaspes, Paurava came to grief for not protecting his flanks. This probably induced Kautilya to come up with wings, which would function as a flank protection force. Machiavelli writes that mercenaries and auxiliaries are useless and dangerous. He goes on to say that wise princes, therefore, have always shunned auxiliaries and made use of their own forces.161 As regards the army, which constitutes an important part of the danda, Kautilya writes:

Inherited from the father and the grandfather, constant, obedient, with the soldiers’ sons and wives contented, not disappointed during marches, unhindered everywhere, able to put up with troubles, that has fought many battles, skilled in the science of all types of war and weapons, not having a separate interest because of prosperity and adversity shared with the king, consisting mostly of the Kshatriyas – these are the excellences of an army.162

Kautilya is for recruiting troops from all four varnas163 in order to prevent any one community from becoming over-powerful in the state. Machiavelli comments that natural courage is inadequate. Military success depends on order and discipline. For maintaining military discipline, Machiavelli, like the Legalists, focuses on harsh punishment.164 Machiavelli stresses the importance of training.165 Kautilya also emphasizes training of the men and animals in the army.166 Even with all these improvements, Kautilya was not confident that the Mauryan military machine could successfully counter the horse archers and the phalangites. Hence, instead of following a battle-centric strategy, Kautilya advocated kutayuddha.

For both Clausewitz and Jomini, deception in warfare has limited value.167 Kautilya introduces the concept of samdhaya yayat, which means downright duplicity. It involves making peace and then attacking the enemy when he is least expecting such an attack.168 Information warfare is a strong point with Kautilya. For waging information warfare, Kautilya advocates the use of various types of spies to gather knowledge about different aspects of the hostile polities. In 1620, Roger Bacon wrote that ‘knowledge and human power are synonymous, since the ignorance of the cause frustrates the effect.’169 However, Clausewitz disdains the role of intelligence (both battlefield and strategic) in warfare.170

Kautilya, Thucydides and Clausewitz all focus on the intangible aspects of warfare: morale and the psychology of the commander and the men under arms. Machiavelli, like Georg Heinrich von Berenhorst (1733–1814) in 1797, anticipated Clausewitz by emphasizing the role of moral and psychological factors in warfare.171 Like Clausewitz, Berenhorst gives importance to the personality of the ruler and to chance and accidents.172 Both Kautilya and Clausewitz give importance to the commander. Kautilya’s vijigishu is comparable to Clausewitz’s genius for war who rises above all rules.173 Clausewitz’s concept of genius for warfare is derived from Immanuel Kant’s writings. The latter wrote that genius is a talent for producing for which no definite rule can be given.174 Clausewitz’s ‘genius for war’ is somewhat equivalent to the utsahasakti of Kautilya’s vijigishu. In his 1804 notes, Clausewitz uses the word Intelligenz to describe the commander’s rational thinking. The personality of the commander is not peripheral but central to Clausewitz’s theory of warfare.175 Clausewitz emphasizes the importance of decisiveness and daring on the part of the commander.176 On War tells us: ‘Strength of character does not consist solely in having powerful feelings, but in maintaining one’s balance in spite of them.’177 Clausewitz speaks of ‘the play of chance and probability within which the creative spirit is free to roam.’178

Clausewitz also speaks of kleine krieg (little war), which refers to the use of small detachments for skirmishing, harassing and gathering information about the movement of enemy troops.179 In the case of a popular uprising (similar to Kautilya’s kopa), the personalities of the leaders and public opinion constitute, for Clausewitz, the centre of gravity.180 At times, for Clausewitz, the enemy’s centre of gravity becomes the leader of a rebellious group, that is, a popular charismatic ruler.181 Hew Strachan writes that, inspired by the uprising of nationalist guerrillas in Spain and Tyrol against the Napoleonic occupation armies, Clausewitz drew up plans for forming militias that would unite the people in arms with the ‘national’ army challenging the occupying force.182 Clausewitz incorporated irregular warfare within his concept of volkskrieg (people’s war). Irregular warfare involves popular participation. People’s war also involves a wide range of popular involvement in warfare. In Clausewitz’s paradigm, the militia should be used in conjunction with the regular army. Clausewitz identified several conditions necessary for generating guerrilla warfare: war on one’s own territory, a large theatre of operations with rough and inaccessible terrain, and a people whose temperament is suited to irregular warfare. For Clausewitz, guerrilla warfare (he has Prussia in mind) is the weapon of last resort, to be used when everything else has failed.183

Clausewitz writes that there are two types of war: war designed to destroy the enemy politically and militarily, and war designed to occupy some portion of the enemy’s territory. In the case of the first type of war, the victor dictates peace, and in the case of the second type of war, peace is negotiated.184 When absolute war aimed at the complete shattering of the enemy is not possible, then war with a limited aim should be pursued. Limited war is characterized by delaying engagements, since the aim of the weak defender is to avoid decisive battles at all cost. In a limited war, the defender retreats inside his own territory and the strength of the attackers gradually decreases. The defender takes advantage of the local terrain and delays the attacker with small delaying parties until the culmination point of the attack has passed and the attacking party exhausts itself. At that critical juncture, the defender should switch to the offensive mode of warfare.185

Before the First World War, Hans Delbruck, a veteran of the Franco-Prussian War and an academician, argued that if Clausewitz were alive, he would have developed a system that recognized two different forms of waging war. The first is described as the strategy of annihilation, and the second is the strategy of exhaustion, which is designed to wear out the enemy so that the latter is forced to negotiate.186 As we will see in the next section, Sun Tzu, the most famous ancient Chinese theoretician, and Kautilya are indeed followers of what Delbruck categorized as the strategy of exhaustion.

(This article is a republished version of chapter 3 from the author’s work titled ‘Hinduism and the ethics of warfare in south Asia‘)

Disclaimer: The opinions expressed in this article are solely the author’s and do not neccessarily reflect the opinions or beliefs of the website and its affiliates.

Bibliography

113 Hew Strachan, Clausewitz’s On War: A Biography (New York: Atlantic Monthly Press, 2007), pp. ix, 32.

114 Hugh Smith, On Clausewitz: A Study of Military and Political Ideas (Houndmills, Basingstoke: Palgrave, 2005), p. 3.

115 Carl Von Clausewitz, On War, ed. and tr. by Michael Howard and Peter Paret (1984; reprint, Princeton, New Jersey: Princeton University Press, 1989), p. 63.

116 Heuser, Reading Clausewitz, p. 204.

117 Clausewitz, On War, ed. and tr. by Howard and Paret, p. 69.

118 Ibid., p. 87.

119 Ibid., p. 87.

120 Heuser, Reading Clausewitz, p. 53.

121 Clausewitz, On War, ed. and tr. by Howard and Paret, p. 89.

122 Michael I. Handel, ‘Clausewitz in the Age of Technology’, JSS, vol. 9, nos. 2–3 (1986), pp. 74–5. Hew Strachan argues that Clausewitz did not write about the superiority of the politicians over the generals but emphasizes close interaction between the top civilian authority and the generals. Strachan, Clausewitz’s On War, p. 168.

123 Strachan, Clausewitz’s On War, p. 91.

124 Handel, ‘Clausewitz in the Age of Technology’, p. 79.

125 Strachan, Clausewitz’s On War, pp. 83, 88.

126 Chakravarti, Art of War in Ancient India, p. v.

127 Clausewitz, On War, ed. and tr. by Howard and Paret, p. 75.

128 Ibid., p. 95. Italics in original.

129 Heuser, Reading Clausewitz, p. 9.

130 Handel, Masters of War, p. 40.

131 Alan Beyerchen, ‘Clausewitz and the Non-Linear Nature of Warfare: Systems of Organized Complexity’, in Hew Strachan and Andreas Herberg-Rothe (eds.), Clausewitz in the Twenty-First Century (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2007), pp. 45, 51.

132 Handel, Masters of War, 41.

133 Clausewitz, On War, ed. and tr. by Howard and Paret, p. 99.

134 Ibid., p. 71.

135 Ibid., p. 76.

136 Ibid., p. 80.

137 Heuser, Reading Clausewitz, pp. 91–3. Some scholars interpret On War by arguing that Clausewitz emphasizes defence rather than offence as the stronger form of war.

138 KA, Part III, by Kangle, p. 264.

139 Chakravarti, Art of War in Ancient India, p. vii; David Kahn, ‘Clausewitz and Intelligence’, JSS, vol. 9, nos. 2–3 (June–Sept. 1986), p. 122.

140 Gilbert, ‘Machiavelli’, pp. 24–5.

141 Jha, Early India, p. 83.

142 J. R. Hamilton, ‘The Cavalry Battle at the Hydaspes’, Journal of Hellenic Studies, vol. 76 (1956), pp. 26–7.

143 Majumdar, Military System in Ancient India, p. 49.

144 A. K. Srivastava, Ancient Indian Army: Its Administration and Organization (New Delhi: Ajanta Publications, 1985), p. 38.

145 Hamilton, ‘Cavalry Battle at the Hydaspes’, pp. 27, 30–1.

146 Stanley J. Olsen, ‘The Horse in Ancient China and Its Cultural Influence in Some Other Areas’, Proceedings of the Academy of Natural Sciences of Philadelphia, vol. 140, no. 2 (1988), p. 176.

147 Chakravarti, Art of War in Ancient India, p. 25.

148 Bimal Kanti Majumdar, The Military System in Ancient India (Calcutta: Firma KLM, 1960), p. 50.

149 Bonnerjea, ‘Peace and War in Hindu Culture’, p. 36.

150 Mital, Kautilya Arthasastra Revisited, p. 25.

151 Olsen, ‘Horse in Ancient China and Its Cultural Influence’, pp. 173–4, 185.

152 Murray B. Emeneau, ‘The Composite Bow in India’, Proceedings of the American Philosophical Society, vol. 97, no. 1 (1953), p. 80.

153 Kosambi, Culture and Civilization of Ancient India, p. 135.

154 Emeneau, ‘Composite Bow in India’, p. 85.

155 Majumdar, Military System in Ancient India, p. 50.

156 Bonnerjea, ‘Peace and War in Hindu Culture’, p. 37.

157 Majumdar, Military System in Ancient India, p. 50.

158 Bonnerjea, ‘Peace and War in Hindu Culture’, p. 36.

159 Chakravarti, Art of War in Ancient India, p. 86.

160 KA, Part III, by Kangle, p. 259.

161 Machiavelli, The Prince, pp. 77, 84.

162 KA, Part II, by Kangle, p. 316.

163 KA, Part III, by Kangle, p. 143.

164 Gilbert, ‘Machiavelli’, in Paret (ed.), Makers of Modern Strategy, p. 25.

165 Machiavelli, The Prince, pp. 88–9.

166 Kautilya, The Arthasastra, ed., rearranged, tr. and introduced by L. N. Rangarajan (New Delhi: Penguin, 1992), pp. 692–4.

167 Handel, Masters of War, pp. 33, 122.

168 KA, Part II, by Kangle, p. 333.

169 Quoted in Martin Van Creveld, ‘The Eternal Clausewitz’, JSS, vol. 9, nos. 2–3 (June– Sept. 1986), endnote 12, p. 49.

170 Kahn, ‘Clausewitz and Intelligence’, p. 117.

171 Strachan, Clausewitz’s On War, p. 83; Heuser, Reading Clausewitz, p. 80.

172 Heuser, Reading Clausewitz, p. 9.

173 Katherine L. Herbig, ‘Chance and Uncertainty in On War’, JSS, vol. 9, nos. 2–3 (June– Sept. 1986), p. 103.

174 Heuser, Reading Clausewitz, p. 72.

175 Strachan, Clausewitz’s On War, pp. 92–3.

176 Smith, On Clausewitz, p. 11.

177 Clausewitz, On War, ed. and tr. by Howard and Paret, p. 107.

178 Ibid., p. 89.

179 Smith, On Clausewitz, p. 10.

180 Handel, Masters of War, p. 45.

181 Heuser, Reading Clausewitz, p. 76.

182 Strachan, Clausewitz’s On War, p. 52.

183 Smith, On Clausewitz, pp. 32–3.

184 Strachan, Clausewitz’s On War, p. 73.

185 Heuser, Reading Clausewitz, pp. 96, 103.

186 Strachan, Clausewitz’s On War, p. 17.