The debate regarding the dating and authorship of the Arthasastra continues. Thomas Trautmann argues that the Kautilya Arthasastra is actually a composite product of three or four different individuals. In Trautmann’s view, Kautilya is at best a compiler and editor of the teachings of previous teachers belonging to the arthasastra tradition.1 In a somewhat similar vein, D. N. Jha writes that computer analysis shows that there are three distinct styles in the Arthasastra, but that Books 2, 3 and 4 have a distinct Mauryan touch and constitute the kernel of the Arthasastra.2

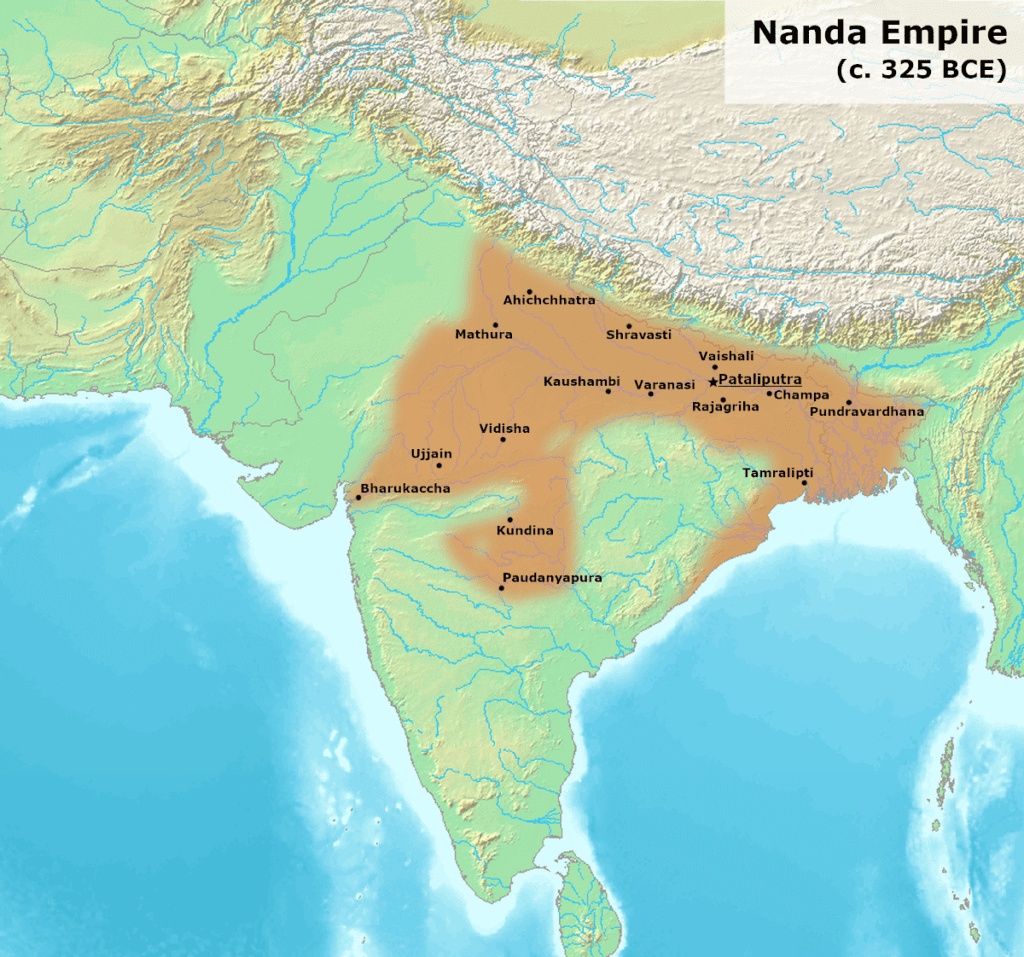

Related to the problem of authorship, the author’s background is also shrouded in mystery. According to one tradition, Kautilya (also known as Chanakya and Vishnugupta) was a learned Brahmin of eastern India who served the Nanda Dynasty of Magadha but left the Nandas due to some personal problems. According to another version, Kautilya hailed from Taxila, an important cultural centre in Pakistan’s Punjab, about twenty miles north-west of Rawalpindi. On his own initiative, he became a councilor of Chandragupta Maurya, the founder of the Maurya Empire.3 P. V. Kane, following the Buddhist and Jain traditions, suggests that Kautilya probably hailed from Gandhara.4 The Bhagavata Purana says that a Brahmin named Chanakya destroyed the Nandas and coronated Chandragupta, whose son was Bindusara and whose grandson was Asoka.5 Overall, the Puranas and Mahavamsa equate Chanakya with Kautilya. In general, historians agree that Kautilya played a very important part in the success of Chandragupta (320–297/6 BCE). P. V. Kane claims that the Arthasastra was composed between 320 and 300 BCE. Some scholars point out that if the Arthasastra was the product of Kautilya, why does Megasthenes, the Seleucid ambassador to the Maurya court, never mention Kautilya? Kane says that it is because in 302 BCE, when Megasthenes came to India, Kautilya had retired from public life.6 Narasingha P. Sil assumes that towards the end of Chandragupta’s reign, Kautilya fell out with his royal master and left the Maurya capital of Pataliputra (near Bankipur on the river Ganga in Bihar) and retired to private life. The Arthasastra was probably composed during Kautilya’s retirement from the court at Pataliputra.7 Secondly, only fragments of Megasthenes’ work has survived. So, we cannot be sure whether Megasthenes did know of Kautilya Arthasastra.

Origin and Scope of Arthasastra

Kautilya’s work did not develop in a vacuum. The theory of polity – that is, the genre known as arthasastra – emerged as early as 600 BCE.8 Kautilya quotes several individual predecessors, including Pisuna, Bharadvaja, Kaninka, Vatavyadhi, and Visalaksa, most of whom belonged to the arthasastra tradition. Arthasastra is the name of the work composed by Kautilya, but it also refers to a genre of classical Hindu literature. In Kane’s view, arthasastra is narrower in scope than dharmasastra but broader than dandaniti. Overall, arthasastra comprises politics, economics, law and justice.9 Arthasastra means labha (the theory of politics for acquisition, i.e., the theory of the acquisition of political power and economic resources) and palana (good governance, i.e., the protection of material goods and the king’s subjects).10 ‘Economics and the theory of politics are the only sciences’, say the followers of Brihaspati.11 ‘The theory of politics is the true knowledge’, say the followers of Usanas (a pre-Kautilyan political thinker). The school of the Usanas continues: ‘For with it are bound up undertakings connected with all the knowledge systems.’12 Kautilya says: ‘Since with their help one can learn what is spiritual good and material well-being, therefore the knowledge systems (vidyas) are so called. Samkhya, Yoga and Lokayata – these constitute philosophy.’13 Kautilya attempts to put forward the timeless laws of politics, economy, diplomacy and war.14

Kautilya’s work contains fifteen adhikaranas (books). The first five books deal with the internal administration of the polity, and the next eight deal with foreign relations. The last two books are miscellaneous in character. Book 7 deals especially with foreign policy and the use of stratagems and force for gaining objectives. Books 9 and 10 deal with military preparations for the vijigishu (ruler with hegemonic ambitions). Book 12 shows how a weak king should survive against a strong king. Book 13 mainly describes siege warfare.15

The Arthasastra is written in prose, with verses scattered at the middle or end of chapters.16 The geographical scope of Kautilya’s theory encompasses the whole subcontinent. Kautilya praises high-value commodities from different parts of South Asia. He refers to silk from Magadha (Bihar) and Kasmira (Kashmir), cloth from Vanga (West Bengal and Bangladesh), and gems and diamonds from Vidharbha, Kalinga (Orissa), Kosala and Kasi.17 Kautilya was also aware of the neighbouring countries of India. The Arthasastra speaks of silk from Cinas (China) and blankets from Nepal.18

Kautilya’s work does not refer to any particular historical event. This is because in ancient India, according to the tradition of the sastras, great works expounding timeless principles were always compiled by some mythical sage. In such works, any reference to historical individuals or events is inconceivable, as any such reference would reduce the value of the work.19 Kautilya may not have mentioned historical events, but no theorist could remain unaffected by the surrounding historical context and the contemporary material culture. In addition to the pre-existing political theories in India, Kautilya’s ideas are also shaped by his immediate historical background, which is the focus of the next section.

The Economic, Political and Military Background

After late in the sixth century BCE, Magadha emerged as the most powerful mahajanapada. Bimbisara, the ruler of Magadha (546–494 BCE), was known as seniya (one with sena). D. N. Jha asserts that Bimbisara was probably the first ruler in India with a regular standing army. Bimbisara annexed Anga. Bimbisara’s son and successor, Ajatasatru, not only fortified Rajagriha (the capital of Magadha) with a forty-kilometer-long wall but also sent one of his ministers (a Brahmin named Vassakara) to sow dissension among the Lichchhavi tribes.20 Ajatasatru was able to overthrow the Vajjis through the policy of bheda followed by Vassakara.21 Kautilya’s concept of kutayuddha was probably shaped by such historical events.

In 413 BCE, Shishunaga, the viceroy/governor of Benaras, became the ruler, and in 321 BCE the Shishunaga dynasty was overthrown by Mahapadma Nanda. Mahapadma, a Sudra, not only annexed Kalinga but also increased the strength of the army.22 The Vishnu Purana and the Brahmanda Purana say that the Nandas ruled for 100 years.23 Alexander crossed the Hindu Kush Mountain range in 327 BCE, but he then left after a brief sojourn in north-west India. Hence, no direct confrontation between the Greeks and the Nanda Empire occurred.

Chandragupta, like Mahapadma Nanda, was a Sudra. Chandragupta’s mother, Mura, was probably the daughter of a Persian merchant. Reflecting the historical reality, the Arthasastra, unlike the vedas, never argue that the vijigishu should always come from the Kshatriya rank. Chandragupta seized Magadha around 321 BCE. By 312 BCE, he had completed the conquest of north and north-west India. If we believe the Mudraraksa (a fictional political drama in Sanskrit, by Vishakadatta, composed between the fourth and the seventh century CE), Chandragupta probably first acquired Punjab and then, with the help of Chanakya, moved towards the Nanda Empire. Paurava, who was ruling as a client ruler on behalf of Alexander, was killed before 318 BCE. The Mudraraksa tells us that Chandragupta, with the aid of some mercenaries from the north-west frontier tribes, laid siege to Kusumapura, the capital of Magadha. In the Questions of Milinda there is a reference to Bhaddasala, a general belonging to the Nandas, who fought against Chandragupta. Chandragupta defeated Seleucus in 305 BCE in a series of encounters along the river Indus. Megasthenes came to the Maurya court as an ambassador around 302 BCE and resided in India for four years. Around 297 BCE, Chandragupta passed away.24

As regards the nature of the Maurya Empire, historians are divided into two camps. While R. K. Mookerji25 and D. N. Jha argue that it was a centralized empire, Gerard Fussman26 and Burton Stein27 claim that the Maurya Empire was a decentralized political entity. Some factual statements point to the fact that the Maurya Empire was a centralized bureaucratic polity. The Mauryas, like the Romans, were great road builders, and all the roads led to Pataliputra. Megasthenes noted that the thousand-mile-long royal highway connected Pataliputra to Taxila.28 Pataliputra was connected to Nepal via Vaishali. From there a road passed through Champaran to Kapilavastu, Kalsi (DehraDun District), and Hazara up to Peshawar. Another network of roads connected Pataliputra to Sasaram, Mirzapur and central India. Yet, another road connected Pataliputra to Kalinga, Andhra and Karnataka, the southernmost limit of the empire.29 These roads, besides facilitating trade and commerce, also functioned as military highways.

Jha claims that the Maurya economy was a sort of command economy. The Maurya polity exercised rigid control through a number of super-intendents who presided over all trade and commercial activities. The metallurgy and mining industries were highly developed and were state monopolies. The monopoly rights of the state over mineral resources gave it exclusive control over the manufacture of metal weaponry.30 However, at times, mining was leased out to contractors. India produced high-quality steel, and the metal workers of Asia Minor adopted the techniques of Indian steel making.31 Kautilya tells us about a die-striking (punch-marking) system but is unaware of casting coins in mould.32 The Magadhan state functioned as a cash economy.33 Money was used for trade as well as for paying the state’s civilian and military officials.34

Megasthenes tells us that soldiers were paid and equipped by the state. Hence, it seems that the Mauryas maintained a standing army and not merely a militia.35 On the other hand, opines P. C. Chakravarti, the existence of armed trade and craft guilds with their private militias points to the fact that the Maurya Empire was a weak state. Not only did the private militias of these armed srenis provide protection to these organizations from brigands and highwayman, but during emergencies the ruler also hired them to fight internal as well as external enemies. These armed guilds occasionally engaged in private warfare and, in a way, constituted semi-autonomous states within a state.36 It seems that the Mauryan Empire was not uniformly administered and was partially centralized and partially decentralized.

Romila Thapar takes a middle position and claims that the level of control exercised by the Maurya central government over different regions varied with distance. The inner core of the Maurya Empire was the metropolitan state of Magadha, which was ruled directly by the emperor from Pataliputra. Beyond the metropolitan state was the outer core of the empire, which comprised north and central India. The outer core region was divided into several provinces ruled by viceroys appointed by the emperor at Pataliputra. Most of the viceroys were princes of the royal family. The control of the central government at Pataliputra over the outer core region was substantial, but less than its control over the metropolitan state. Beyond the outer core was the periphery, which was comprised of north-west India and Deccan (the region south of the Narmada River). The periphery was ruled by several hereditary vassal chiefs and tribal leaders who accepted the political suzerainty of the Mauryan emperor at Pataliputra. It goes without saying that the control exercised by the central government at Pataliputra over the distant periphery was weakest. The central government did not interfere in the internal affairs of the vassal kingdoms, but it did control the foreign and military policies of the vassal chiefs.37 This three-tier model of Thapar seems to be the most appropriate one for explaining the structure of the Maurya Empire. It is to be noted that the Arthasastra also speaks of regions ruled directly by the vijigishu; the janapadas (fertile agricultural land dotted with urban centres), which were ruled by chiefs and officials appointed by the vijigishu and hereditary vassal chiefs; and the forest regions under indirect control of the vijigishu. As a basis of comparison, the Shang Empire of China seems to have been more centralized than the Mauryan Empire because the former political entity had the capacity to conscript the common people for civil engineering projects and distributed grain through a system of centrally administered state granaries.38

Buddhism focused mainly on moksa. The arthasastra school, asserts Sil, emerged as a reaction to Buddhism. The arthasastra tradition emphasizes materialism rather than morality. The arthasastra writers divide the goals of human life into chatuvarga (four categories): dharma (morality), artha (wealth), kama (desires) and moksa. And of these four, artha occupies the most prominent place. Kautilya himself says that material well-being is supreme, because spiritual well-being and sensual pleasures depend on material well-being. The arthasastra means the sastra (theory) of artha. The meaning of artha changes with circumstances; broadly, it refers to wealth and territory with human population. Kautilya’s Arthasastra does not really deal with the theory of the generation of wealth but is a treatise on statecraft. Kautilya says that the source of the livelihood of men is wealth and that the means for the attainment and protection of artha constitutes the theory of politics. Kautilya aims to educate the prince on the acquisition of material welfare (labha) and its maintenance through good governance.39 The objective of Kautilya’s theory is to lay bare the study of politics, wealth and practical expediency. The subjects covered are administration, law, order and justice, finance, foreign policy, internal security and defence against external powers.40 The arthasastra tradition, claims Ashok S. Chousalkar, is based on the Lokayata philosophy, which emphasized analysis of concrete facts. The Lokayatas deduced their conclusions from human behaviour and attempted an inductive investigation of the polity.41 In the following sections, Kautilya’s philosophical ideas are compared to and contrasted with both Western and Chinese philosophies.

(This article is a republished version of chapter 3 from the author’s work titled ‘Hinduism and the ethics of warfare in south Asia‘)

Disclaimer: The opinions expressed in this article are solely the author’s and do not neccessarily reflect the opinions or beliefs of the website and its affiliates.

Bibliography

1 Surendra Nath Mital, Kautilya Arthasastra Revisited (2000; reprint, Centre for Studies in Civilizations, distributed by Munshiram Manoharlal: New Delhi, 2004), pp. 106, 111.

2 D. N. Jha, Early India: A Concise History (New Delhi: Manohar, 2004), p. 96.

3 Narasingha P. Sil, Kautilya’s Arthasastra: A Comparative Study (Calcutta/New Delhi: Academic Publishers, 1985), p. 19.

4 P. V. Kane, History of Dharmasastra (Ancient and Medieval Religious and Civil Law in India), vol. 1, Part 1 (1930; reprint, Poona: Bhandarkar Oriental Research Institute, 1968), pp. 173, 214–15.

5 Mital, Kautilya Arthasastra Revisited, p. 60.

6 Kane, History of Dharmasastra, vol. 1, Part 1, pp. 172, 184–5, 215.

7 Sil, Kautilya’s Arthasastra, pp. 19–20.

8 The Kautilya Arthasastra (hereinafter KA), Part III, A Study, by R. P. Kangle (1965; reprint, New Delhi: Motilal Banrasidas, 2000), p. 11.

9 Kane, History of Dharmasastra, vol. 1, Part 1, pp. 152–3.

10 Mital, Kautilya Arthasastra Revisited, p. 65

11 The Kautilya Arthasastra, Part II, An English Translation with Critical and Explanatory Notes, by R. P. Kangle (1972; reprint, Delhi: Motilal Banarasidas, 1992), p. 6.

12 My translation differs from that of Kangle. KA, Part II, by Kangle, p. 6.

13 My translation differs from that of Kangle. KA, Part II, by Kangle, p. 6. In the manuscript, the term vidya is used. Instead of the term ‘science’ which Kangle uses, I prefer the term ‘knowledge system’.

14 Roger Boesche, ‘Kautilya’s Arthasastra on War and Diplomacy in Ancient India’, JMH, vol. 67 (Jan. 2003), p. 15.

15 KA, Part III, by Kangle, pp. 19–20.

16 Kane, History of Dharmasastra, vol. 1, Part 1, p. 197.

17 Mital, Kautilya Arthasastra Revisited, p. 25.

18 Kane, History of Dharmasastra, vol. 1, Part 1, p. 211

19 KA, Part III, by Kangle, p. 63.

20 Jha, Early India, pp. 84–6, 90.

21 KA, Part III, by Kangle, p. 11.

22 Jha, Early India, p. 87.

23 Mital, Kautilya Arthasastra Revisited, p. 60.

24 Kane, History of Dharmasastra, vol. 1, Part 1, pp. 173–4, 184, 186, 217–18.

25 R. K. Mookerji, Chandragupta Maurya and His Times (n.d.; reprint, New Delhi: Motilal Banrasidas, 1960).

26 Gerard Fussman, ‘Central and Provincial Administration in Ancient India: The Problem of the Mauryan Empire’, Indian Historical Review, vol. 14, nos. 1–2 (1988), pp. 43–72.

27 Burton Stein, A History of India (1998; reprint, New Delhi: Oxford University Press, 2004), pp. 78–83.

28 Mital, Kautilya Arthasastra Revisited, p. 29.

29 Jha, Early India, p. 102.

30 Ibid., pp. 102–5.

31 Mital, Kautilya Arthasastra Revisited, p. 32.

32 Sil, Kautilya’s Arthasastra, p. 25.

33 D. D. Kosambi, The Culture and Civilization of Ancient India in Historical Outline (n.d.; reprint, New Delhi: Vikas, 2001), p. 154.

34 Jha, Early India, p. 102.

35 Biren Bonnerjea, ‘Peace and War in Hindu Culture’, Primitive Man: Quarterly Journal of the Catholic Anthropological Conference, vol. 7, no. 3 (1934), p. 36.

36 P. C. Chakravarti, The Art of War in Ancient India (1941; reprint, New Delhi: Low Price Publications, 1989), pp. 6, 8.

37 Romila Thapar, The Mauryas Revisited (1987; reprint, Calcutta: K. P. Bagchi & Company, 1993).

38 Thomas M. Kane, Ancient China on Postmodern War: Enduring Ideas from the Chinese Strategic Tradition (London/New York: Routledge, 2007), p. 29.

39 Sil, Kautilya’s Arthasastra, pp. 20–1.

40 Rashed Uz Zaman, ‘Kautilya: The Indian Strategic Thinker and Indian Strategic Culture’, Comparative Strategy, vol. 25, no. 3 (2006), p. 235.

41 Ashok S. Chousalkar, A Comparative Study of Theory of Rebellion in Kautilya and Aristotle (New Delhi: Indological Book House, 1990), p. 65.