Kautilya as a Realist Philosopher and a Theorist of Power

Realist theorists of international relations assume that the state is a unitary actor with coherent objectives and a centralized capacity to act on its decisions.42 The Realist School argues that the behaviour of states is shaped by the power at their disposal in the fiercely competitive international environment. Actions undertaken by a polity for defensive purposes may be seen by others as posing an offensive threat.43 The measures that one state takes to increase its security in an insecure world often decrease another state’s security, even if that is not intended. One’s strength may be another’s weakness. Each side fears the other, but every step that one side takes to strengthen security scares the other into similar steps, and vice versa, in a continuing escalating spiral. For the polities, there is no escape from the system. This is known as a ‘prisoner’s dilemma’, fuelled by mutual suspicion. As absolute security is difficult to achieve, constant warfare may be waged, conquests carried afar and power accumulated, all motivated by security concerns – that is, for defence.44 The actors in the international state system pursue gain-maximizing behaviour and have difficulty effecting cooperation.45 This is because, in the realist paradigm, the international state system is a self-help system, and today’s friends and allies could become tomorrow’s enemies.46 In the brutish world where today’s friends may be tomorrow’s enemies, states are more concerned with relative gains than with absolute gains.47 The standard realist assumption is that states are rational unitary actors calculating, under conditions of uncertainty, the costs and benefits of peace and war.48 And going to war at any given time could be a rational and even an optimal option.49

The realist thinkers from Niccolo Machiavelli (1469–1527 CE) and Thomas Hobbes through Hans Morgenthau, Robert Gilpin and John Mearsheimer have observed that self-interested rulers pursue opportunistic expansion, which constitutes the driving force behind realpolitik competition. Victoria Tin-Bor Hui writes that classical Western thinkers like Machiavelli and Hobbes emphasized both passions and interests. My take is that both these thinkers, like Kautilya, focused more on interests than on emotions and passions. Kenneth Waltz somewhat revises the classical insights and suggests that rational states seek to maximize security rather than power, because security is the highest end, while power is a means to an end. Waltz continues that states at a minimum seek their own preservation and at a maximum drive for universal dominion50 that will give them total security. This is exactly the point that Kautilya pushes. The neo-realist approach assumes that states seek power. The offensive realists argue that states pursue power not only for security but also for acquiring hegemony in the inter-state arena, since only a hegemon is truly secure.51 The defensive realists argue that states attempt to expand when expansion increases their security, and offensive realism argues that a state’s capabilities shape its intentions. It will expand when it can. However, Mearsheimer, an advocate of offensive realism, accepts the idea that the fundamental objective behind state behaviour is survival.52 Kautilya, like the realists, believes that the world is full of disorder, anarchy and chaos. The ultimate security for the polities in such an anarchic inter-state system is power. The mandala (circle of states with the vijigishu at the centre) system is a fluid one and the relationships among the various states are always changing, thus creating danger for some and opportunities for others.53 The international system, in Kautilya’s eyes, is characterized by matsanya (the law of the pond, where bigger fish gobble up smaller fish). In other words, the inter-state system is characterized by chaos, and the only operating principle is ‘might is right’.54

In contrast to the Upanishads, which pushes a metaphoric attitude towards violence, Kautilya presents an instrumental view of organized violence: state interests and the careful calculation of a cool strategist.55 The mandala theory is essentially a doctrine of strife and struggle. Usanas notes that a king who refuses to fight is swallowed up by the earth just as a rat swallows a mouse.56 Like the Namierites, Kautilya does not believe in any ideology behind human actions.57 Kautilya says that the foreign policy of a vijigishu should be shaped by the self-interest of the state. Kautilya speaks of karmasandhi, that is, a treaty signed with a ‘natural’ enemy in order to tide over emergencies and to protect the state.58 The implication is that such treaties are to be torn apart at the first possible opportunity. Francis X. Clooney S.J. asserts that Kautilya advocates preemptive strikes in order to protect the kingdom from external enemies.59 Preventive war is war waged to arrest the growth of a hostile military power through bold and timely action, exploiting one’s advantage while one can. By contrast, a pre-emptive strike is an attack against the enemy for the purpose of self-defence, when a massive enemy attack is almost certain to come and could not be effectively checked.

Kautilya claims that dandaniti is the principal instrument for acquisition of things not possessed, for protection of things one possesses and for augmentation of things one would like to possess.60 Like a true realist, Kautilya says:

Power is the possession of strength. Success is obtaining happiness. Power is threefold: the power of knowledge is the power of counsel, the power of the treasury and the army is the power of might, the power of valour is the power of energy. In the same way, success is also threefold: that attainable by the power of counsel is success by counsel, that attainable by the power of might is success by might, that attainable by the power of energy is success by energy.61

Roger Boesche writes that the goal of the science of politics for Kautilya, as for Hobbes, is power.62

In the Shantiparva of the Mahabharata, Bhisma, somewhat like a neo-realist theorist, advises Kshatriya to acquire power because a powerful person is the master of everything. Further, wealth strengthens power. Bhisma goes on to say that power is superior to dharma because in the final analysis, dharma is protected by power. This trend of thinking is further developed in the Arthasastra. Kautilya, like Bhisma, accepts the importance of power in public life. Taking a statist perspective, Kautilya writes that ‘The king, the ministers, the kingdom, the fortified cities, the treasury, the army and the ally, are the constituent elements of the state.’63 However, Bhisma says that if dharma and power are associated with truth, then this troika becomes invincible.64 This point is not accepted by Kautilya. He separates political action from religious speculations, urging the vijigishu to depend on the theory of artha rather than on religious precepts.65

At times, during periods of international anarchy, cooperation among some states becomes possible. A would-be hegemon could be deterred by the formation of an anti-hegemonic coalition, and if deterrence failed, then the hegemon could actually be pushed back by a military defeat inflicted upon him by the coalition.66 Here lies the importance of diplomacy for establishing the balance of power in the international arena. And Kautilya’s Arthasastra gives a lot of space to the balancing behaviour of weak states as a means of survival in the anarchic world. As regards the role of allies, Kautilya’s opportunism is revealed in the following words: ‘The ally giving the help of money is preferable. For the use of money is made at all times, only sometimes that of troops. And with money, troops and other objects of desire are obtained.’67 Tasamantah is the neighbour of the weak king whose overthrow has brought the vijigishu into contiguity with him. Hence, he now becomes the enemy of the vijigishu when formerly he was his ally, being one state away.68

Theodore George Tsakiris asserts that the Greek historian Thucydides is the founding father of political realism. He is principally a theorist who utilizes the empirical evidence of the Peloponnesian War to validate his own abstract conceptualizations as regards power, human nature and the dynamics of war and peace.69 Thucydides is a narrative historian rather than a philosophical analyst like Kautilya. Still, this historian’s views regarding warfare and strategy need to be assessed in relation to Kautilya’s concepts. Thucydides writes that in making a case study of the Athens-Sparta conflict, he is dealing with the theme of the origins of war, a theme that is of timeless relevance. In his History of the Peloponnesian War, Thucydides recounts the tragedy of human action in a world of powerful forces beyond human control. For Thucydides, the major motives for going to war are land disputes, past injuries and hegemonic ambitions.70 The fundamental drives defining the behaviour of states are ambition, fear and self-interest fuelling the state’s perennial quest for power. In Thucydides’ framework, states have to achieve their objectives within an antagonistic, perfidious and anarchic international system. Thucydides derives his political realism from the Greek philosopher Heracleitus (500 BCE), who claims that war is synonymous with the perpetual state of political antagonism determining the relation of states in a condition of political anarchy. Heracleitus contends that war is the father of all things, and that war is unavoidable and necessary for perpetuating the equilibrium of the international system.71 Thucydides’ history analyzes the political, social and moral-psychological dynamics that generate aggression, violence and the desire for domination and revenge. Unlike Kautilya, Thucydides assumes that the long-term security of a state depends on moderation and the preservation of representative institutions that are particularly geared toward protecting the poor.72 Thucydides’ hero Pericles emphasizes that Athens’ greatness depends on the personal courage of the citizens rather than on guile.73 It seems that Thucydides is a supporter of heroic warfare, that is, dharmayuddha, which Kautilya critiques.

The classic realist thinker is Machiavelli. Hence, a detailed comparison of Kautilya and Machiavelli will be fruitful. Machiavelli was born in Florence in 1469 of an old citizen family. In 1498, he was appointed secretary and second chancellor to the Florentine Republic. In accordance with the duties of his office, he led several diplomatic missions to Louis XII, Emperor Maximilian, Julius II and others. In 1507, as chancellor of the newly appointed Nove di Milizia, he organized an infantry force that fought with the army that captured Pisa in 1509.

B. N. Mukherjee writes that Machiavelli was the Kautilya of the West.74 For Machiavelli, power is an end in itself. Machiavelli’s The Prince (1513), like the Arthasastra, investigates ways to acquire, retain and expand power. His prince prefers fear to love from his subjects. Sil claims that Machiavelli’s image of the prince was modelled on the personality of Asiatic conquerors like Genghis Khan and Timur, who were regarded as the very embodiment of force and fear.75 Machiavelli, in his Discourses, writes that a combination of force and fraud will overwhelm the enemy.76

In The Prince, Machiavelli writes: ‘The fact is that a man who wants to act virtuously in every way necessarily comes to grief among so many who are not virtuous. Therefore, if a prince wants to maintain his rule, he must learn how not to be virtuous.’77 Machiavelli elaborates: ‘Everyone realizes how praiseworthy it is for a prince to honour his word and to be straightforward rather than crafty in his dealings; nonetheless contemporary experience shows that princes who have achieved great things have been those who have given their words lightly, who have known how to trick men with their cunning, and who in the end, have overcome those abiding by honest principles.’78 He sums up:

… a prudent ruler cannot, and must not, honour his word when it places him at a disadvantage and when the reasons for which he made his promise no longer exist…. Because men are wretched creatures who would not keep their word to you, you need not keep your word to them…. Those who have known best how to imitate the fox have come off best. But one must know how to colour one’s actions and to be a great liar and deceiver. Men are so simple, and so much creatures of circumstances, that the deceiver will always find somebody ready to be deceived.79

Machiavelli notes that there are two ways of fighting: by law or by force. The first way is natural to men, and the second to beasts. But as the first way often proves inadequate, one must sometimes have recourse to the second. So, a prince must understand how to make a nice use of the beast and the man.80 These two sorts of war are somewhat equivalent to Kautilya’s dharmayuddha and kutayuddha. One type of kutayuddha is asurayuddha, which, in terms of its amoral approach and lethality, is equivalent to Machiavelli’s fighting like a beast. Kautilya says that the vijigishu should make use of both dharmayuddha and asurayuddha in accordance with the circumstances. Both Kautilya and Machiavelli believe that the end justifies the means. Both agree on the utilization of wine, women, poison and spies for the attainment of one’s objectives.81

For Machiavelli, war is a tool of politics.82 Machiavelli gives prime importance to armies and warfare in his paradigm of power-politics. He asserts:

A Prince, therefore, must have no other object or thought, nor acquire skill in anything, except war, its organization, and its discipline. The art of war is all that is expected of a ruler; and it is so useful that besides enabling hereditary princes to maintain their rule it frequently enables ordinary citizens to become rulers. On the other hand, we find that princes who have thought more of their pleasures than of arms have lost their states. The first way to lose your state is to neglect the art of war; the first way to win a state is to be skilled in the art of war.83

Machiavelli wants the war to be short and sharp.84 Kautilya realizes that wars cannot always be short. Kautilya introduces the concept of ekatra, which means an expedition for a single specific objective. And anekatra refers to more than one objective, which in turn requires fighting simultaneously in various places.85 While undertaking an expedition, Kautilya warns that the vijigishu should leave behind one-third to one-fourth of the troops for the purpose of protecting his base.86

Rather than pure force, Kautilya advises the vijigishu to use economic welfare in conjunction with force to maintain his power. It is to be noted that for Kautilya, bala (army) is less important than kosa (treasury). Kautilya says that an army can be raised and maintained from a well-filled treasury for maintaining dharma, but not vice versa.87 In Kautilya’s paradigm, prabhavasakti (the combined power of the army and treasury) is more important than mantrasakti (diplomacy) and utsahasakti (the personal energy and drive of the ruler).88

Kautilya not only attempts to conceptualize the nature of war, both within and among the states, but also tries to formulate a strategy of power. He attempts to create a systematic and universal theory of power and warfare that will be applicable in all environmental contexts. The lynchpin of Kautilya’s paradigm is the assumption that human beings crave power, the most vital component for survival in the big bad cosmos. One could argue that, like the Enlightenment theorists, Kautilya is trying to formulate a theory of power/security based on universal, time-less and ‘scientific’ principles that will hold true for all ages.89

Torkel Brekke criticizes Kautilya by saying that the power and influence of the kings in the international order described by Kautilya overlap and interpenetrate in ways with internal enemies in ways that make it impossible to distinguish between external and internal affairs.90

Brekke, in another article, argues that Kautilya fails to distinguish between policing and war.91 A world of self-interested actors is a world of dog-eat-dog competition, not only in interstate relations but also in state-society relations, writes Victoria Tin-Bor Hui. If a ruler betrays his allies and breaks his word in the international realm, he is also likely to subjugate his citizens in the domestic realm. The state becomes something like a predatory mafia. Victoria Tin-Bor Hui writes that a dynamic theory should view politics – both international and domestic – as a process of strategic interaction between domination seekers and targets of domination.92

Thucydides harps on the change in the international balance of power that creates insecurity for a state, but he also stresses the importance of domestic politics (demagogues, passions, emotions and perceptions, i.e., the role of subjective human agency) in shaping the foreign policy of a polis.93 Thucydides points out that external war causes internal strife within the polis. 94 Machiavelli also notes the linkages between internal security and external security. He says that there are two things a prince must fear: internal subversion from his subjects, and external aggression by foreign powers. Against the latter, his defence lies in being well armed and having good allies; and if he is well armed, he will always have good allies. In addition, domestic affairs will always remain under control provided that relations with external powers are under control, and if the rebels were not disturbed by a conspiracy sponsored by a foreign power. Machiavelli notes that if the prince imposes excessive taxes on the people, his reputation will decline. This will result in his subjects turning against him, and he will be generally despised.95

Kautilya links up kopa within the state with intervention by the foreign powers. In other words, Kautilya is making a linkage between internal rebellion and the shifting power structure in the international arena. Kautilya authorizes the vijigishu to pursue an expansionist design as regards foreign affairs and total suppression of the civil society in order to weed out any possibility of kopa. The Arthasastra discusses kopa from the perspective of state security. The principal danger to the state, writes Kautilya, comes from prakriti kopa. This means the anger or wrath of the people when they lose faith in the established government, which in turn affects the legitimacy of the government. While analyzing the factors behind kopa, says Chousalkar, Kautilya focuses mainly on the individual actors rather than on the social and class factors. The Arthasastra takes a top-down approach. Kautilya asserts that the leaders of the rebellion are not thrown up spontaneously from below; rather, they are disgruntled elites of the state like the yuvaraj (crown prince), the mantri (minister) and the senapati (general).96 Ajatasatru (ruled 493–461 BCE) came to power after killing his father, Bimbisara. After Ajatasatru’s death in 461 BCE, he was succeeded by five kings, all of whom came to power by killing their fathers. Kautilya’s recommendations in the Arthasastra that a king should sow dissension among his enemies and must always guard against fratricide were probably shaped by the above-mentioned historical circumstances.

Hui criticizes Western international theories by stating that a theory should be more attentive to agency in order to explain changes in both the international and domestic realms. However, most Western international theories focus on structure rather than agency. The structuralists claim that individuals are embedded in their social environments and collectively shared systems of meanings. Structural realism claims that states make policy choices subject to the constraints they face. Hui writes that institutions are simultaneously enabling and restricting. She goes on to say that strategic mistakes made by an actor or a cluster of actors can fundamentally alter the trajectory of the whole system.97 Machiavelli and Kautilya act as a corrective to the structuralism inherent in recent international theories. Overwhelming importance is given to the prince’s and vijigishu’s actions and personalities in The Prince and in the Arthasastra.

Of the qualities of a successful ruler, Machiavelli writes: ‘He will be despised if he has a reputation for being fickle, frivolous, effeminate, cowardly, irresolute; a prince should avoid this like the plague and strive to demonstrate in his actions grandeur, courage, sobriety, strength.’98 Kautilya rejects astrology (meaning luck) as a way to understand fate.99 Kautilya’s philosophy calls for paurusha (manliness/courage) plus action and not resignation on the part of the vijigishu.

Kautilya’s Arthasastra and the Western Political Philosophers and Historians

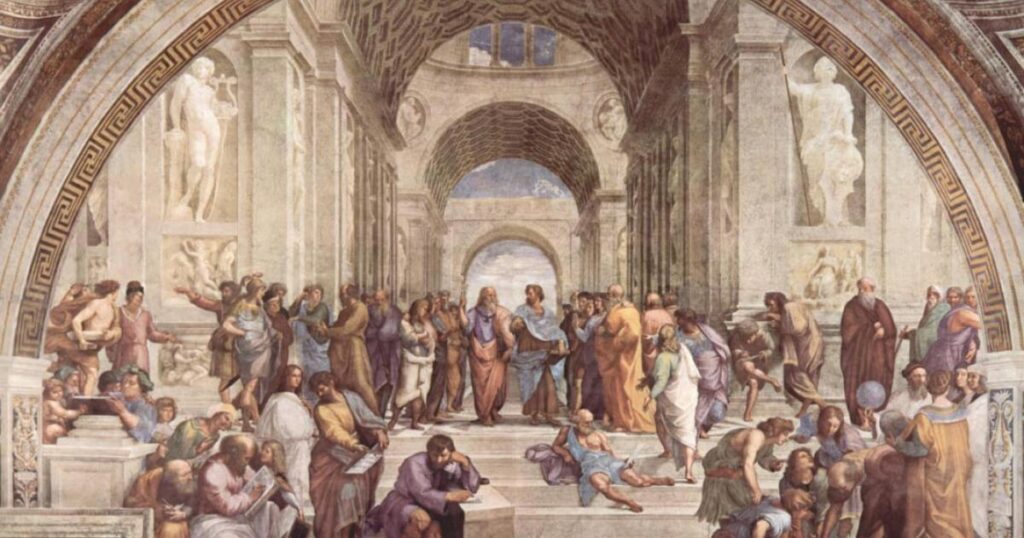

Plato (c. 429/7–347 BCE) and Aristotle (384–322 BCE) were near contemporaries of Kautilya.100 So Kautilya’s Arthasastra could be compared to and contrasted with the Republic, Statesman and Laws of Plato and the Politics of Aristotle. Plato entered public service in Athens when the city was under the rule of the Thirty Tyrants installed by Sparta. He withdrew to Megara after the execution of his friend cum philosopher Socrates (470–399 BCE). However, Plato returned to Athens in 387 BCE and started a garden school on the outskirts of Athens near the shrine of Academus, a local hero. In this academy, selected young men were taught Socratic philosophy and Pythagorean mathematics. On Alexander’s death in 323 BCE, Plato was forced to leave Athens by the anti-Macedonian party and died in exile at Chalcis. Plato is skeptical of the common man and his virtues and values. Democracy, in Plato’s eye, is nothing more than a sort of anarchy, because the common man is a bundle of unrestrained appetites, and his behaviour is dependent on the pleasure of the moment. The content of Plato’s politics is autocratic, but it forces the philosopher-king to become a politikos for leading a life not of unmitigated luxury but of discipline and austerity, that is, a sort of military monasticism.101

Similarly, Kautilya advises the ruler to control his senses in order to direct the administration vigorously and to endear himself to his people. Kautilya lays down a detailed routine for the vijigishu: overseeing the collection of revenue, inspecting the military forces, listening to the reports of spies during the night and delegating tasks to secret agents and so on.102 Kautilya warns that too much indulgence in kama (sex) by the vijigishu would result in disruption of governance.103 Like Plato, Kautilya writes that common people’s minds are not steady and that their behaviour is inconsistent.104 Hence the vijigishu, implies Kautilya, should depend on danda rather than on the goodwill of the masses.

Aristotle was born at Stagira on the Chalcidic Peninsula of Thrace and was the son of the royal physician of Macedon. He entered Plato’s academy at the age of seventeen and studied there for the next twenty years until Plato’s death. He left when Plato’s nephew Speusippus was elected as the head of the academy. For the next two years, Aristotle lived with Hermias, a slave turned tyrant in Asia Minor. Hermias’ adopted daughter became Aristotle’s wife. For next three years, Aristotle served as tutor to the young Alexander of Macedon; in 335 BCE he set up his Lyceum between Mount Lycabettus and the river Ilissus, north-east of Athens. This academy became a rival of Plato’s academy.105 For Aristotle, all sciences have a practical orientation. Each techne (art/science) has to perform a certain task in order to achieve a certain telos.106 Kautilya says: ‘Philosophy is ever thought of as the lamp of all sciences, as the means of all actions and as support of all laws and duties.’107

Kautilya is a supporter of the monarchical form of government and accepts, like Aristotle, that in the last instance the ruler is dependent on the suffrage of the ruled. Both the Mahabharata and the Arthasastra express a dislike of tyrants. Kautilya says that while tyrants are interested in self-aggrandizement, monarchs are more focussed on the interests of the polity. For Plato and Aristotle, power is a means to achieving a high end – the happiness of the citizens. Both Kautilya and Aristotle emphasize that moderation in the use of force ensures the stability and longevity of regimes. Kautilya warns the king to use danda with a sense of discrimination and by steering a middle course. The theory of the divine origin of the king in the Kautilyan tradition is slightly different from the Western theory. In the ancient Indian context, the king is divine not because he is a god in human form but because he protects the lives and properties of his subjects along with the varna society. As long as he is pursuing his duties, the king observes dharma and is a righteous king and thus a divine monarch. If he fails to discharge his duties properly, then he ceases to be divine.108

Kautilya’s kutayuddha has certain commonalities with the Roman historian Tacitus’ (56 CE–117 CE) description of deceptive warfare. Tacitus, in his Annals, speaks of poisoning among the Parthian ruling elite and the presence of treacherous subordinates.109 The Arthasastra introduces the concept of tusnimdandena, which means getting rid of enemy leaders by assassination, poisoning and so forth.110 Deceptive techniques were also used by the Romans. In 172 BCE, Marcius Philippus bought time for Rome, during a war with Perseus of Macedonia, by sending a deceptive embassy. And Tacitus saw merit in the Roman Emperor Tiberius’ foreign policy vis-à-vis Parthia, which encouraged the various enemy factions to fight each other rather than directly waging war against them.111

Kautilya elaborates the various components of kutayuddha. Dvaidhibhava is dual policy. It means that maintaining peace with one party while fighting another power, and also outwardly maintaining peace with one power while secretly preparing to attack that power. Dvaidhibhutah is making a pact with the usual enemy in order to make war on another king. When a kalaha (life-and-death struggle) occurs between the enemy and a neighbouring king, the vijigishu sits tight, because a decline in the power of the enemy suits the vijigishu’s interests. Occasionally, the vijigishu also encourages kalaha between two potentially hostile states. Yatavya means a neighbouring prince who is afflicted with problems and hence should be attacked by the vijigishu. 112 Now, let us compare Kautilya to the most famous of the ultra-realist theorists of war of the Western world: Carl von Clausewitz.

(This article is a republished version of chapter 3 from the author’s work titled ‘Hinduism and the ethics of warfare in south Asia‘)

Disclaimer: The opinions expressed in this article are solely the author’s and do not neccessarily reflect the opinions or beliefs of the website and its affiliates.

Bibliography

42 Victoria Tin-Bor Hui, War and State Formation in Ancient China and Early Modern Europe (New York: Cambridge University Press, 2005), p. 15.

43 Bruce Russett, ‘Thucydides, Ancient Greece, and the Democratic Peace’, JME, vol. 5, no. 4 (2006), p. 255.

44 Azar Gat, War in Human Civilization (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2006), pp. 98–9.

45 Hui, War and State Formation in Ancient China and Early Modern Europe, p. 13.

46 Russett, ‘Thucydides, Ancient Greece, and the Democratic Peace’, p. 260.

47 Hui, War and State Formation in Ancient China and Early Modern Europe, p. 27.

48 Russett, ‘Thucydides, Ancient Greece, and the Democratic Peace’, p. 255.

49 Gat, War in Human Civilization, p. 100.

50 Hui, War and State Formation in Ancient China and Early Modern Europe, pp. 13–14.

51 Rajesh Rajagopalan, Fighting like a Guerrilla: The Indian Army and Counterinsurgency (London/New York/Delhi: Routledge, 2008), pp. 30, 74.

52 Hui, War and State Formation in Ancient China and Early Modern Europe, p. 14.

53 Zaman, ‘Kautilya’, pp. 236–7, 240.

54 KA, Part III, by Kangle, p. 116.

55 Laurie L. Patton, ‘Telling Stories about Harm: An Overview of Early Indian Narratives’, in John R. Hinnells and Richard King (eds.), Religion and Violence in South Asia: Theory and Practice (London/New York: Routledge, 2007), p. 24.

56 Chakravarti, Art of War in Ancient India, p. 181.

57 Chousalkar, Theory of Rebellion in Kautilya and Aristotle, p. 77.

58 KA, Part III, by Kangle, pp. 93–4, 118.

59 Francis X. Clooney S.J., ‘Pain but Not Harm: Some Classical Resources towards a Hindu Just War Theory’, in Paul Robinson (ed.), Just War in Comparative Perspective (Aldershot: Ashgate, 2003), p. 116.

60 Sil, Kautilya’s Arthasastra, p. 23.

61 KA, Part II, by Kangle, p. 319.

62 Boesche, ‘Kautilya’s Arthasastra’, p. 15.

63 KA, Part II, by Kangle, p. 314.

64 Chousalkar, Theory of Rebellion in Kautilya and Aristotle, p. 66.

65 Boesche, ‘Kautilya’s Arthasastra’, p. 15.

66 Hui, War and State Formation in Ancient China and Early Modern Europe, pp. 17, 24.

67 KA, Part II, by Kangle, p. 350.

68 Ibid., p. 353.

69 Theodore George Tsakiris, ‘Thucydides and Strategy: Formations of Grand Strategy in the History of the Second Peloponnesian War (431–404 BC)’, Comparative Strategy, vol. 25, no. 3 (2006), p. 173.

70 Eric Robinson, ‘Thucydides and Democratic Peace’, JME, vol. 5, no. 4 (2006), p. 250.

71 Tsakiris, ‘Thucydides and Strategy’, pp. 174–5.

72 David Cohen, ‘War, Moderation, and Revenge in Thucydides’, JME, vol. 5, no. 4 (2006), p. 285.

73 Russett, ‘Thucydides, Ancient Greece, and the Democratic Peace’, p. 258.

74 B. N. Mukherjee, ‘Foreword: A Note on the Arthasastra’, in Sil, Kautilya’s Arthasastra, p. xi.

75 Sil, Kautilya’s Arthasastra, p. 8.

76 Michael I. Handel, Masters of War: Classical Strategic Thought (1992; reprint, London: Frank Cass, 1996), p. 123.

77 Niccolo Machiavelli, The Prince, tr. with an Introduction by George Bull (1961; reprint, Harmondsworth, Middlesex: Penguin, 1981), p. 91.

78 Ibid., p. 99.

79 Ibid., pp. 99–100.

80 Ibid., p. 99.

81 Chakravarti, Art of War in Ancient India, p. vii.

82 Beatrice Heuser, Reading Clausewitz (London: Pimlico, 2002), p. 44.

83 Machiavelli, The Prince, p. 87.

84 Felix Gilbert, ‘Machiavelli: The Renaissance of the Art of War’, in Peter Paret (ed.), Makers of Modern Strategy from Machiavelli to the Nuclear Age (1986; reprint, Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1990), p. 24.

85 KA, Part II, by Kangle, p. 333.

86 Chakravarti, Art of War in Ancient India, p. 93.

87 G. N. Bhat, ‘Means to Fill the Treasury during a Financial Crisis – Kautilya’s Views’, in Dr. Michael (ed.), The Concept of Rajadharma (New Delhi: Sundeep Prakashan, 2005), p. 148.

88 KA, Part III, by Kangle, pp. 128–9.

89 For the scientific rationalism of the Enlightenment, see Julian Reid, ‘Foucault on Clausewitz: Conceptualizing the Relationship between War and Power’, Alternatives, vol. 28, no. 1 (2003), p.11.

90 Torkel Brekke, ‘The Ethics of War and the Concept of War in India and Europe’, NUMEN, vol. 52 (2005), p. 80.

91 Torkel Brekke, ‘Wielding the Rod of Punishment – War and Violence in the Political Science of Kautilya’, JME, vol. 3, no. 1 (2004), p. 46.

92 Hui, War and State Formation in Ancient China and Early Modern Europe, pp. 2, 15.

93 Russett, ‘Thucydides, Ancient Greece, and the Democratic Peace’, pp. 255, 265.

94 Cohen, ‘War, Moderation, and Revenge in Thucydides’, p. 280.

95 Machiavelli, The Prince, pp. 92, 103.

96 Chousalkar, Theory of Rebellion in Kautilya and Aristotle, pp. 48, 50, 74, 76–7, 80.

97 Hui, War and State Formation in Ancient China and Early Modern Europe, pp. 19–21, 23.

98 Machiavelli, The Prince, p. 102.

99 Chakravarti, Art of War in Ancient India, p. 95.

100 Mukherjee, ‘Foreword’, p. x.

101 Sil, Kautilya’s Arthasastra, pp. 26–7, 37, 39, 45.

102 Nirmala Kulkarni, ‘Daily Routine of a King in Kautilya Arthasastra’, in Michael (ed.), Concept of Rajadharma, pp. 144–5.

103 J. S. Negi, ‘Religion and Politics in the Arthasastra of Kautilya’, in Negi, Some Indological Studies, vol. 1 (Allahabad: Panchananda Publications, 1966), p. 20.

104 Sil, Kautilya’s Arthasastra, p. 39.

105 Ibid., p. 45.

106 Tsakiris, ‘Thucydides and Strategy’, p. 175.

107 KA, Part II, by Kangle, p. 7.

108 Chousalkar, Theory of Rebellion in Kautilya and Aristotle, pp. 50–2, 60, 67–8, 79.

109 Rhiannon Ash, ‘An Exemplary Conflict: Tacitus’ Parthian Battle Narrative (Annals 6.34–34)’, Phoenix, vol. 53, no. ½ (1999), p. 114.

110 KA, Part II, by Kangle, p. 23.

111 Ash, ‘An Exemplary Conflict’, p. 130.

112 KA, Part II, by Kangle, pp. 321, 325, 334, 343.