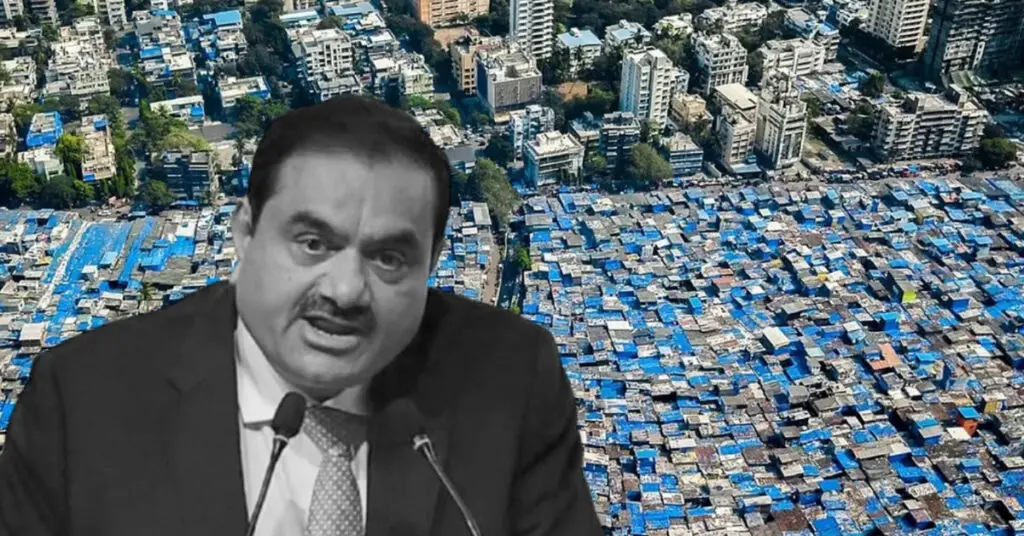

Indian billionaire Gautam Adani’s ambitious plan to overhaul Dharavi, one of Asia’s largest slums, is raising doubts among residents about his ability to execute the project. This skepticism is fueled by recent financial setbacks and allegations of preferential treatment from Prime Minister Narendra Modi’s allies.

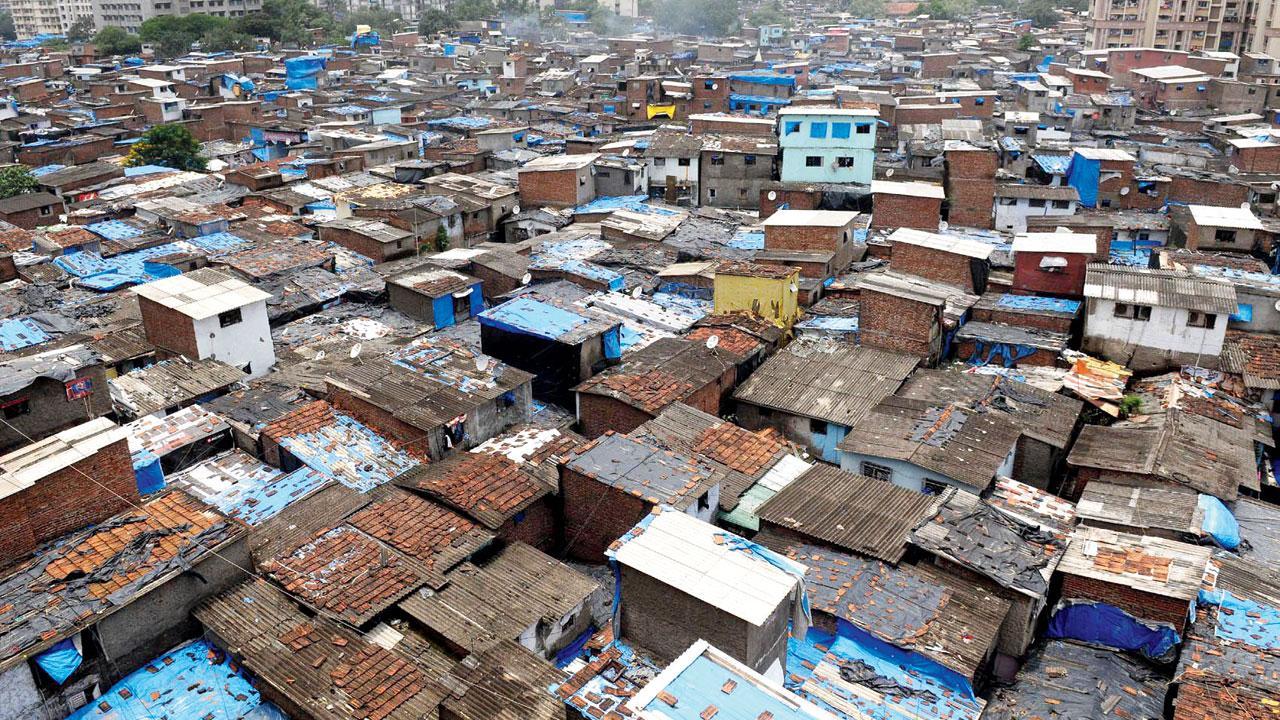

Dharavi, is a sprawling settlement near Mumbai’s international airport, existing in stark contrast to the city’s modern development. As reported by Reuters, Adani’s $614 million contract bid to transform the slum, once known for leather goods production, was approved by the Maharashtra state government in July, following numerous failed previous attempts.

However, concerns that predated this project, primarily related to the complex demographic profile of Dharavi’s residents, persist. The residents of Dharavi find themselves in a paradoxical relationship with Mumbai. On one hand, their struggles for housing rights and improved living conditions have integrated Dharavi into the fabric of the city. Yet, as efforts to transform it into a middle-class “smart city” suburb continue, residents are left in a state of uncertainty.

Critics argue that these plans, including the current one, prioritize profit-making over the welfare of the residents, considering them as an incidental nuisance. A significant portion of Dharavi’s population consists of leather workers from sub-groups of untouchables, Dalits, or Harijans, who migrated to Mumbai from various regions, including Tamil Nadu, Maharashtra, and Bihar. Approximately 29% of Dharavi’s population is Muslim. Additionally, many Dharavi residents maintain ties to their places of origin and engage in circular migration. These connections to their roots, particularly in religious practices, reflect both a sense of identity and a quest for acceptance within wider society. Dharavi’s urban religiosity is closely tied to trans-local and trans-urban connections, emphasizing the need for a deeper understanding of the religious lives of the urban poor in the context of broader affiliations beyond the city.

In her book, Saglio-Yatzimirsky offers insights into the transformation of caste hierarchies in Dharavi. Economic opportunities and education have made caste boundaries more flexible, allowing some individuals to achieve social mobility. The prominence of the leather industry in Dharavi has enabled untouchables to claim artisan status, reducing stigma. However, caste identities continue to play a significant role in social interactions, religion, and marriage arrangements, contradicting predictions of caste disappearance in urban areas. Despite being a slum, Dharavi exhibits remarkable economic vitality, with small leather workshops connecting to national and international markets, challenging stereotypes about slums’ insular economies.

The Adani Group aims to replace the existing “unhygienic, deplorable” conditions with new high-rise towers on state-owned land to accommodate both residents and businesses. The redevelopment, slated to commence in September, is estimated to cost up to $12 billion, potentially yielding revenue of around $24 billion from development rights. However, only residents living in Dharavi before 2000, primarily those on ground floors, will receive free homes within the new development. Approximately 700,000 residents on mezzanine and upper floors are deemed ineligible by the government and may be relocated up to 10 kilometers away, incurring potential upfront costs or higher rents. Some researchers propose an alternative approach where essential infrastructure for water supply and sanitation is provided, development rules are established, and the organizations of residents themselves take up reconstruction as and when they wish, in line with an overall plan.

Residents of Dharavi have voiced their concerns in interviews with Reuters, attributing their uncertainty to Adani’s financial difficulties. Another challenge comes from a legal dispute initiated by rival bidder SecLink Technologies Corporation, alleging unfair treatment and improper cancellation of a 2018 tender in favor of Adani. The Maharashtra government, aligned with Modi’s Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP), is contesting this legal battle. SecLink alleges that the bidding process was manipulated to benefit Adani, a claim that the conglomerate vehemently denies. The Opposition Congress party has seized upon this issue to exert pressure on the ruling BJP in the lead-up to the 2024 national elections.